Miranda rights are the first legal protections provided to suspects as they begin their experience with the legal system in the United States. So how do we ensure that Low English Proficiency (LEP) individuals truly understand these rights while at the same time providing police departments the support they need to deliver Miranda in translation? Student researchers sought possible design-based solutions to this challenge in a project sponsored by the American Bar Association’s Center for Innovation, with input and assistance from the ABA’s Commission on Hispanic Legal Rights and Responsibilities, and in partnership with the New Orleans Police Department.

Understanding Miranda

For suspects, an arrest is a high pressure learning environment where comprehension is paramount. Miranda is often delivered in various contexts based on the assigned job of the police officer and the situation of the arrest. As a result, having an officer read the traditional “Miranda card” is not always the most effective method to ensure a suspect understands his or her rights, as studies show up to 96% of suspects waive their Miranda rights.

Process

The team was led by Jeremy Alexis, Senior Lecturer at IIT Institute of Design, with additional guidance from Harold Krent, Dean of IIT Chicago-Kent School of Law, Denis Weil, Dean of the Institute of Design, and Hugh Musick, Assistant Dean of the Institute of Design. The core team consisted of two ID graduate design students, two undergraduate computer science students from IIT College of Science, and one graduate law student from Chicago-Kent College of Law in Chicago.

Over 11 weeks, the team followed ID’s design process, augmented with agile design techniques. This approach to design created a constant feedback loop within our team and with our clients at the ABA. It was understood that any proposed solution needed to meet basic requirements:

- Be inexpensive

- Be easy to carry and employ “in the field”

- Be easy to use

Through multiple rounds of testing and the introduction of concepts early in their development, we were able to gather feedback and iterate on a micro and macro level. The team developed prototypes for a system of solutions for delivering Miranda in translation.

Miranda Rights in Translation

Outcome: The Benefits of Protoyping

Based on extensive research and consultation with a broad range of stakeholders and police officers in the field who would use the solution, the team developed three technology-enabled tools:

- The Miranda Card, a laminated document with a simple audio module, was the lowest tech option.

- Sit + Watch Miranda was an app-based approach that uses computer stations within police cars to deliver Miranda rights.

- The Miranda App is an interactive tool through which suspects walk through the Miranda warning at their own pace.

Each solution was tested and evaluated by stakeholders. The team ultimately determined that the Miranda Card and Sit+Watch had the greatest potential.

The Miranda Card helps the suspect and police officer follow along the correct path by:

- Providing an explanation of the card and what Miranda rights are.

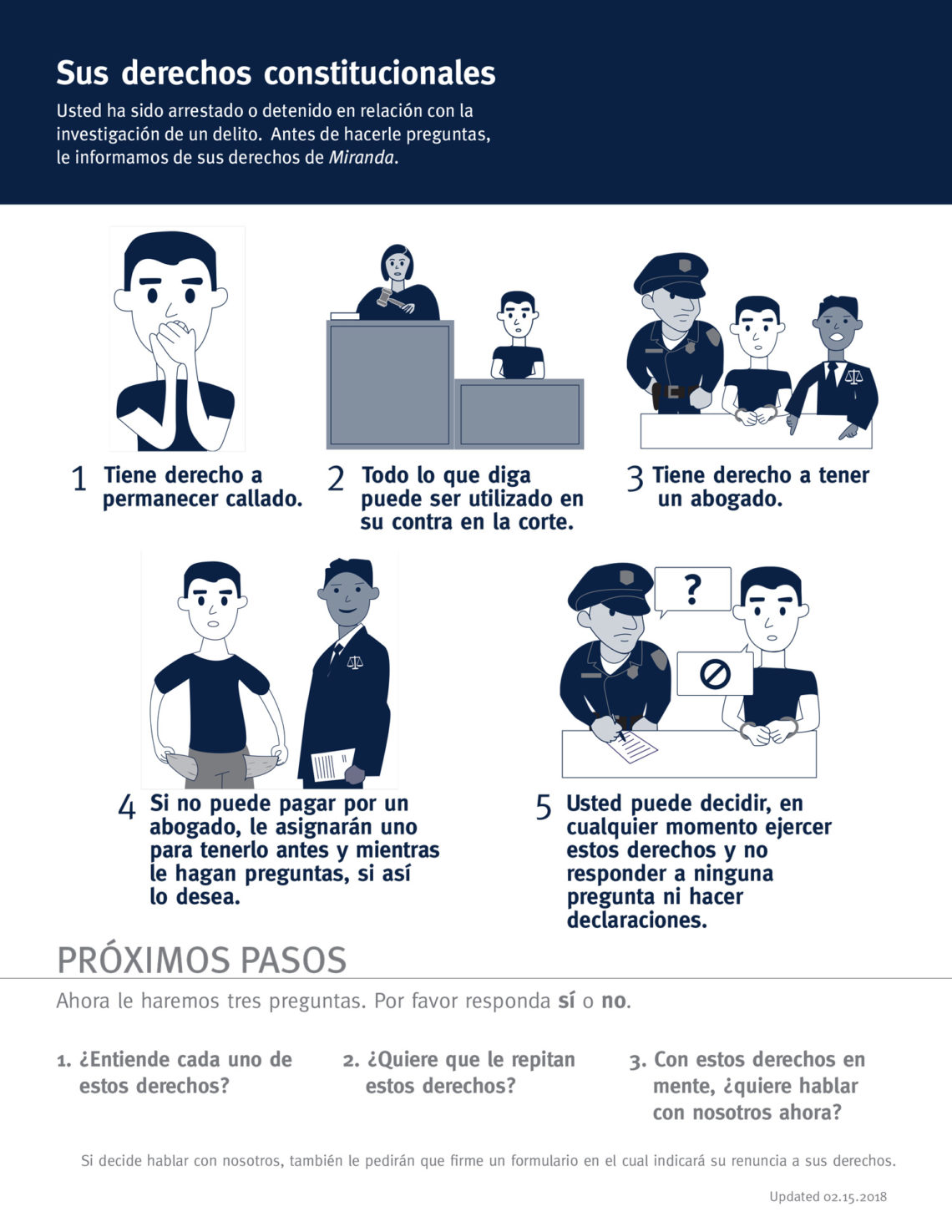

- Articulating in simple, standard language and translations what the Miranda warning is, along with visual cues to help people further understand each right, as well as the three questions asked after Miranda is given.

Along with the text and visuals,a small sound module (similar to those used in “talking” greeting cards) is attached to the back of the Miranda Card, which has a push button that plays audio of all of the text written on the card. The card was designed to be attached to the Plexiglas divider in the back of a police car or windows via suction cups.

At the end of summer 2018, the New Orleans Police Department began testing the two solutions in the field and the ABA is seeking to expand the pilot to other cities. “It’s the beginning of a bigger conversation,” Jeremy Alexis notes. “The idea that technology and innovation can actually begin to influence criminal justice in a very positive way. And it doesn’t have to take a side, it can be good for everybody.”