Jessica Meharry, PhD, Associate Professor, Columbia College Chicago

By Thaddeus Mast

June 21, 2022

Jessica Meharry (PhD 2022) has argued that bias and power asymmetries plague human-centered design, an approach used industry-wide, and she’s working to promote an alternative “anti-oppressive design framework.”

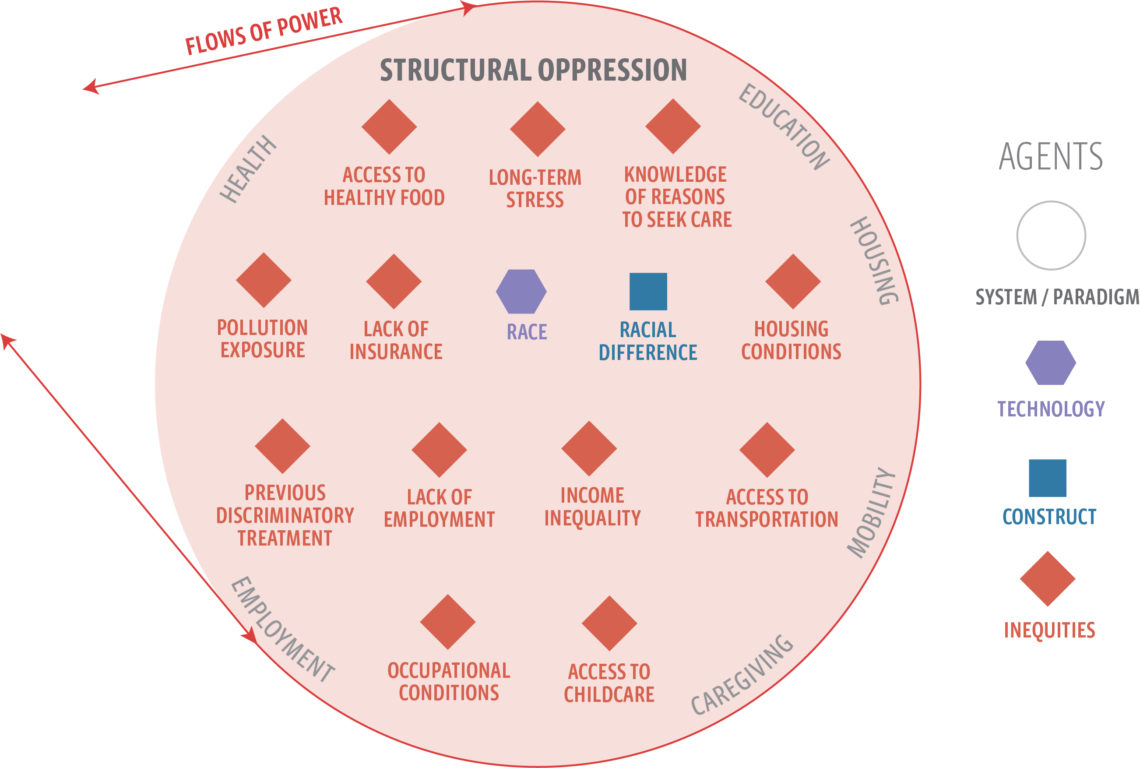

Meharry successfully presented and defended her dissertation, “Sensemaking for Power Asymmetries in Anti-Oppressive Design Practice,” to faculty and peers, most from the Institute of Design, where human-centered design was pioneered and continues to play a key role in the graduate school curriculum. She argues that the methods commonly used to drive the creation and design of new information and communication technologies are leading to global asymmetries in knowledge, information, and power—and that designers might not be aware of the problem or know how to solve it.

After five years as a faculty member teaching design management at Columbia College Chicago, Meharry’s focus shifted in 2018. This was when the college made a concerted effort to become an anti-racist institution and undertook a major diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiative. Meharry sought to connect these efforts to the field of design and design management, but she didn’t know the best way to conduct research and find solutions to DEI problems in design. She looked for a graduate program and found ID.

ID’s reputation played a large part in Meharry’s decision to enroll. “ID is known for its excellent education. It also opens a lot of doors. Professional designers know the institution and its quality, and I was able to talk with a lot of designers I might not have been able to otherwise,” Meharry says.

During her research with professional designers, she found several inherent biases common in standard practices. Sometimes, design methods are too neutral and don’t account for forms of systemic oppression or consider power relations. Others, especially those that use algorithms, might not consider human interactions.

When she began her research, Meharry thought that the results would ultimately upend the current industry standard of human-centered design, which prioritizes the human perspective in the design process and examines how a user would operate a device or interface. Instead, Meharry found that there was room to expand human-centered design to accommodate DEI ideals—especially when it comes to more tech-heavy operations like computer algorithms or artificial intelligence.

“I don’t want to come in and say, ‘Here’s this whole new system,’” Meharry says. “I want to say, ‘Here are some concepts and how you can incorporate some of those ideas.’”

Other students are echoing Meharry’s thoughts about DEI. She says there is a “changing tenor coming into the master’s programs. Students are really getting interested in justice-oriented design.”

Now, Meharry is taking her ideas back to a new role as associate professor and interim co-director of academic diversity, equity, and inclusion at Columbia College Chicago. She will continue her research and work on integrating inclusive approaches into contemporary design practices. “I want to get this work out in the world,” Meharry says.