The Making of The New Bauhaus and László Moholy-Nagy’s Legacy

November 5, 2019

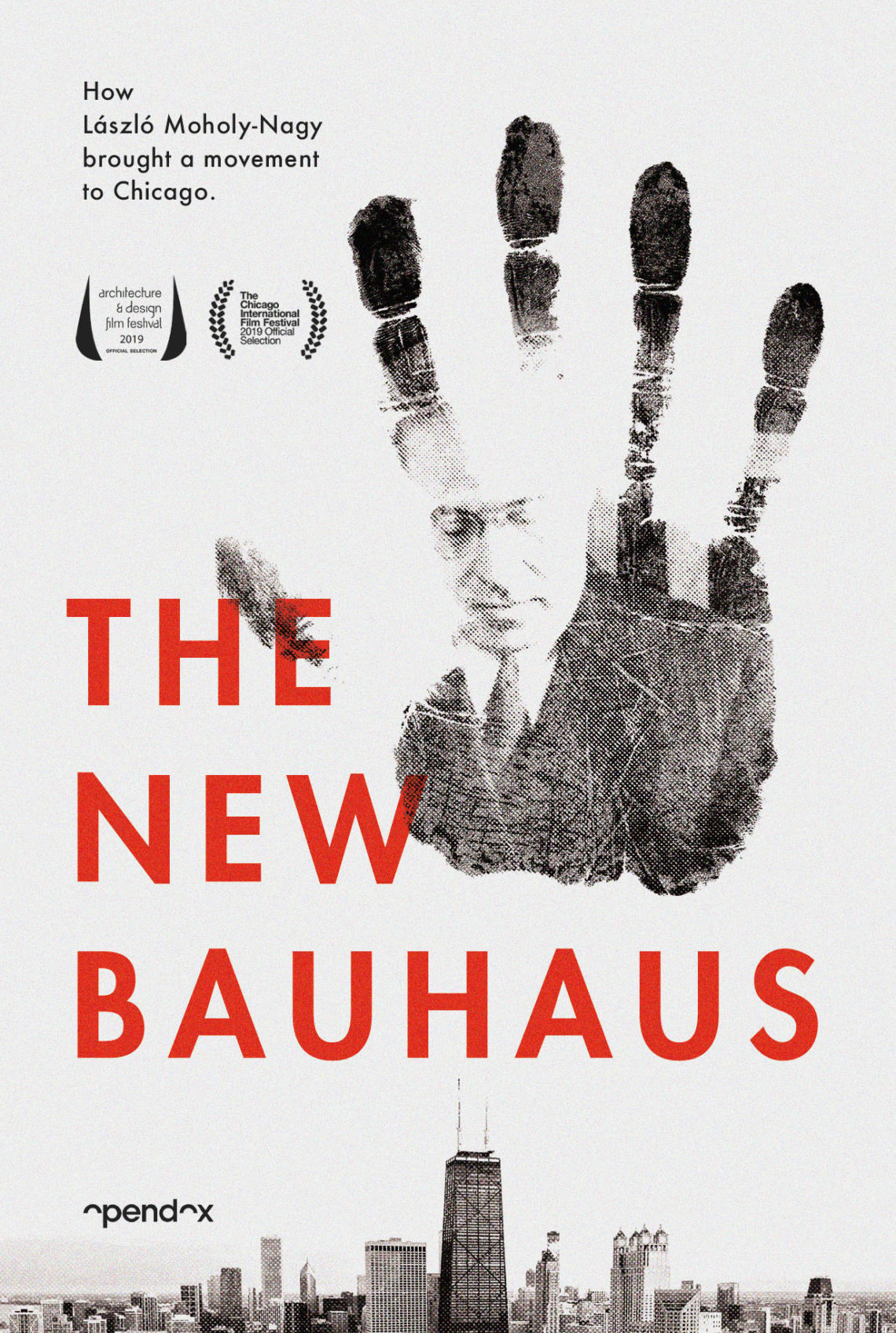

A small documentary film company out of New York started preparing for the Bauhaus centenary in 2016, turning its lens to the Bauhaus’s lesser-known second act in Chicago—The New Bauhaus, by beginning a series of interviews with design experts and historians, collecting archival footage and images supplied by the archives at Illinois Tech’s Illinois Tech’s Paul V. Galvin Library and IIT Institute of Design, and engaging director and filmmaker Alysa Nahmias.

The resulting film from Opendox follows ID’s earliest days, tracing the struggles and triumphs of its founder, László Moholy-Nagy, and revealing his widespread impact on art and design education today.

The most prominent among the film’s many collaborators and advisors is Moholy’s daughter, Hattula. A celebrated academic in the field of archaeology, Hattula Moholy-Nagy has kept a detailed narrative of her father’s life and work since the early 1970s.

Before a screening of The New Bauhaus at the Museum of Contemporary Art in October—on the 82nd anniversary of the day that Moholy first opened ID’s doors—Alysa and Hattula discussed the documentary, as well as Moholy’s life and legacy, with Andrew Connor.

Why do a documentary on László Moholy-Nagy and The New Bauhaus in Chicago now?

Nahmias: I have a background in architecture, and one thing that was interesting to me about the Institute of Design and The New Bauhaus is that I didn’t hear about it. I had heard about Chicago in relation to the Bauhaus in terms of Mies van der Rohe, and I knew that Bauhaus artists had been looking at Chicago, even at the very beginning of the Bauhaus, for examples of innovative modern architecture like Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, but I didn’t even know in all of my education that Moholy-Nagy landed in Chicago and that he founded The New Bauhaus.

I figured if I don’t know about it, other people must not know about it. And then once we started doing a little more investigation, we realized that Hattula is alive and well and has maintained the Moholy[-Nagy] archive and work in such an incredible way. We would have access to this firsthand story, some present tense action that was happening, as well as a wealth of archival material that hadn’t been tapped.

What was it like for you to learn about the Institute of Design? How was working with Hattula?

Nahmias: Working with Hattula was a dream. She is bright, generous, so knowledgeable and funny, and just super-delightful. My whole team and I made many requests of her and she always obliged. I think we had a really good connection as people. I felt like our interviews were much more like conversations, which is how I like it to be. I don’t like it to be Barbara Walters coming into the room. I want it to be very natural and I want people in the theater to feel like they’re in the room with us and are witnessing a kind of heart-to-heart expression of memory and ideas.

If you believe in that talent and cultivate it and work with it and trust it, something interesting will happen. There will be failures, there will be challenges, there will be stumbles, but those things can produce interesting results. I think Hattula and her family, her sons Daniel and Andreas—Andreas who is actually an alum of ID—they really got it. So, me and [producer and cinematographer] Petter Ringbom, who is a designer by background, were working with them, and we all had a common language, I think.

And ID was generous. Adam Strohm, who works in the archive at ID, was so helpful in acquiring high-resolution images. We had numerous ideas and requests, and all of them were met with a real impetus to help and a belief in the project. We did numerous brainstorming sessions with the people who teach and study at ID. We filmed at the school, from Crown Hall to the Kaplan Institute. And it was great to connect with alumni who maybe didn’t feel so connected to the school in a while but perhaps through this project found some newfound connection.

What conclusions did you come to about Moholy’s impact on design education?

Nahmias: One of the big questions we went out to answer in the film [has to do with] the big legacies of The New Bauhaus—there are the various branches in photography, graphic design, industrial design, teaching itself, writing.

It was Moholy’s last work and they all remember buying Vision in Motion or finding it in a library or having a teacher that gave it to them. And it’s this moment they remember decades later because it was so eye-opening.

For a lot of people, they felt less alone as an artist. Because as an artist you may be the only artist in your family or in your school that’s fully devoted to something that’s really against the grain from what society really pushes us toward, because to be an artist is to be an outsider or non-conformist, or [someone who] challenges the norms. And so Vision in Motion is a book I’ve found people have responded to by saying ‘Okay, what I’m doing here is not crazy, or it is crazy, but there are other crazy people out there doing it too.’ And Moholy really embraced that in people.

What was it like living with your father when he first came to Chicago and founded The New Bauhaus?

Moholy-Nagy: I was just a young child at the time. I wasn’t really aware; I was just a little girl. We didn’t see much of him because he was busy. Once the school got going he was there during most of his waking hours. But we went to the school now and again, we were aware of it. There were children’s classes every now and then on Sundays, things like that.

Sometimes his friends from Europe managed to visit; this was World War II times. The Gropiuses came and visited from time to time. They all kept in touch, as émigrés tend to do; they tend to cluster. So, we met these people but it didn’t mean anything then, and by the time it did, they were gone. That’s more or less how it was.

When your mother and sister passed away in 1971, you became the executor of Moholy-Nagy’s estate. What was it like for you, as both an archaeologist and his daughter, to learn more about your father and keep his legacy alive? What was it like working with his colleagues from the Institute of Design?

Moholy-Nagy: These students and ex-faculty that remembered him, they were wonderful. They really helped me organize what memories I did have. They were extremely kind, and it was a good experience.

As I got into it, I learned more and more about him. I read his books and his articles, and talked to the students, so I began to get an idea about his approach and what he was hoping to accomplish.

Is there anything you were surprised to learn about your father?

Moholy-Nagy: I was surprised by what confidence he had. He was sure of his mission, he was sure where he was going, and he had great self-confidence—or if he didn’t, nobody knew. And he just carried on. You have to remember that there was this terrible war going on that took away materials, and money, and manpower, and he just persevered. He never gave up.

Did you get a sense from this experience of your father’s impact on design and education?

Moholy-Nagy: It was subtle. It wasn’t with a lot of fanfare. As Alysa said, she didn’t even know about the school. Most of the successful students became teachers, went out, and sort of spread the word. They started programs at other universities and their design schools. They wrote books and designed things people saw.

What would you like for people watching this documentary to take with them?

Moholy-Nagy: People need to learn to cooperate with each other and get above national concerns.

I would like for them to believe in his mission.