Rob Girling on Designing Radical New Technology ‘At Speed’

April 23, 2019

As a pre-conference 2019 Latham fellow, Rob Girling spoke to the design community at ID on April 2, 2019 about entrepreneurship and emerging technologies, one of the main topics of our 2019 Design Intersections conference (May 22–23).

Rob is co-CEO at Artefact, a design and innovation consultancy. He has 16 years of experience in the field of user experience design and has worked as a design manager at Microsoft, a senior interaction designer at IDEO, and a lead game designer at Sony Computer Entertainment of America. He started his career at Apple after winning its Apple Student Interface Design Competition.

After the Latham lecture, ID associate professor Carlos Teixeira interviewed Rob about his experience working in radical new technology:

Shifting to a systems view: leading methods and processes as co-CEO

Carlos Teixeira: What is the scope of your work at Artefact?

Rob Girling: Artefact is design consultancy in Seattle, about 60 folks. We’ve been around for 12 years, working in digital product design and service design. For most of our life we’ve been following the traditional tropes of aligning human needs and business ambitions in order to define and deliver beautiful, usable, and useful products.

Up until about three years ago that seemed sufficient in terms of challenge. It’s always been difficult enough to do human-centered design well. But given our current global challenges and those just on the horizon, we grew increasingly uncomfortable limiting ourselves to that vantage point.

As part of the technology industry, we wanted to think differently about the collective impacts of the work we are doing, especially at a societal level. We wanted to shift from a product-centric view of what we do to a systems view.

One of things we’ve been struggling with is how to transition our tools and methods from those rooted in products and use cases to a company more focused on thinking about systems and long-term outcomes. That transition is ongoing and will take a long time.

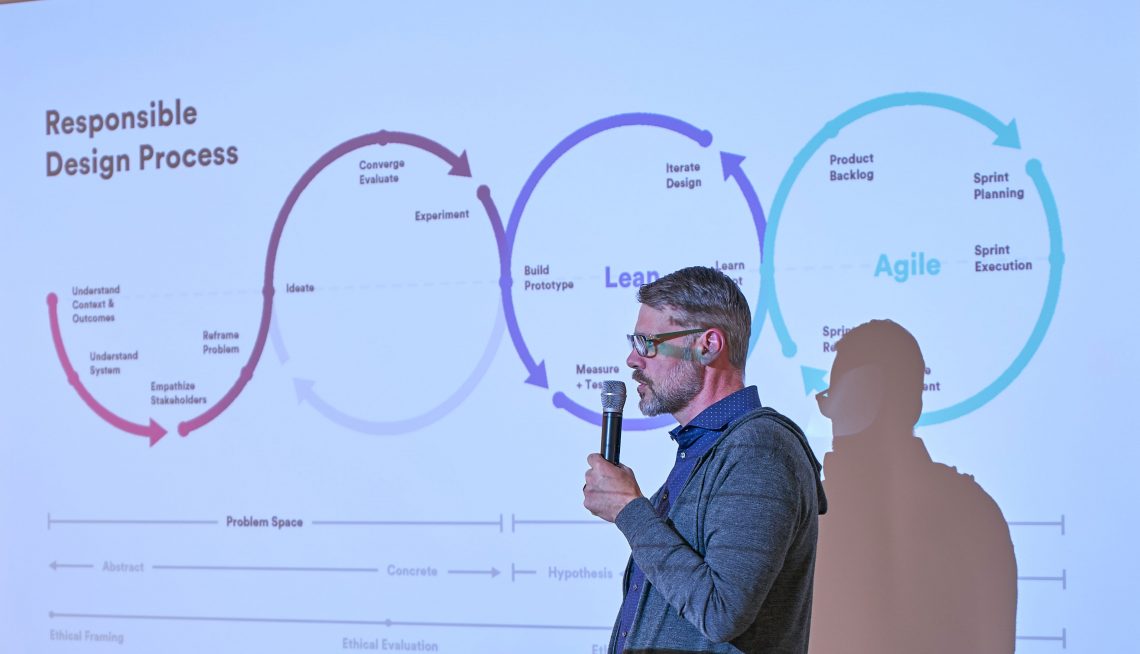

As co-CEO, I’m responsible for thought leadership in the methods and processes space. I’ve been doing a lot of work to pull together a pastiche of techniques and methods that collectively we are putting under the heading of ‘responsible design’ methods.

‘At the very edge of thinking’: Magic Leaps and long-term outcomes

Carlos: You work in a design-driven organization that operates at the cutting edge of emerging technologies and trends. How do you design for radical changes?

Rob: It’s hard to give a general answer to that question because every client brings their own context, momentum, and cultural incentives. But perhaps a good example of working on radical new technology is a client partner that came to us with something that was scarily transformative.

Magic Leap is a very well-known and funded startup that came to us about three years ago. ‘We need help thinking about the fundamentals of interaction in spatial computing,’ they told us. ‘We need an interaction model for how users will interact in mixed reality, and we need an actual system design, complete with user interface.’

We worked closely with Magic Leap’s rapidly growing design team over three years to help craft an experience that stays true to user expectations, while also introducing new behaviors and abilities that are authentic to spatial computing.

It was clear in early ideation sessions just how transformative this type of product could be.

And it didn’t take long for us to discover some really challenging ethical questions with such a new technology. Think about the challenges we have in social media regarding managing content, and then imagine the virtual physical world populated with the internet’s worst inclinations. Should we enable a shared mixed reality environment, where all users can see the same shared reality? If we do, who is allowed and has permission to put things into the world? Can a user attach this virtual review to this restaurant? Is it desirable to allow anyone permission to put my virtual political protest on city hall? And, of course, whose job will it be to govern and police this?

As technology designers trying to design for outcomes in a longer time horizon, it’s clear to me that we have some responsibility to help make the best decisions about a product. That said, it’s especially tricky when the technology is so young, and when you are using clunky backroom prototypes years ahead of release.

As design partners Artefact is right there as part of the client’s team, at the very edge of thinking about this technology. We can see that making the most responsible design call is incredibly hard. Startups especially are rapidly changing environments with evolving teams, changing faces, competing agendas,unclear timelines, and a haste in decision making that makes everyone’s head spin.

Finding North Stars in the Wild West

Carlos: How do you navigate the complexity of large-scale challenges or designing for systemic impact? What are some best practices for achieving successful large-scale collaboration?

Rob: Technology design is not at a mature level. It feels like we are at the end of a Wild West era and just starting to recognize the un-sustainability and undesirability of old approaches.

At Artefact we’re helping leaders of organizations think about long-term preferable outcomes—other than stock value and ROI and other business metrics. This is an idea we borrow from philanthropy, healthcare, and educational circles, trying to define a ‘preferable end state’ and working to create a theory of change to make that possible.

So we start most of our engagements by asking our clients: What are you trying to accomplish in the world? What is the big, audacious, preferable outcome? From there you can root a lot of conversation: Does this help intervention get us one step closer to that or not?

It’s a useful North Star for anchoring conversation, for constantly finding a true path on an uncertain journey.

Secondly I’d say is holistic thinking about stakeholders. In thinking at systems scale, we have to consider all the people impacted, as well as the impact on the environment. We weigh that up in a stakeholder matrix to understand where alignment can happen, where opportunity areas are rich and fruitful for innovation.

These are thoughts that we’ve borrowed from other parts of industry and academia to help do important design work in tech at speed.

Another area is ethics: how do we practically apply ethical frameworks at speed? How do we fairly decide what is most preferable? Of those stakeholders impacted, who carries the benefits and who shares the burdens of technological disruption? There are dozens of these decisions that can be made in a product cycle.

We have developed some techniques to practically evaluate whether idea A is better than idea B through a specific ethical framing. It feels hard to do that responsibly at speed, especially when there are lots of variables that you don’t fully understand.

Searching for the strongest signal

Carlos: How do the scale of the projects you are working on affect your practice? What are the benefits and pitfalls of addressing large numbers of stakeholders?

Rob: One of the benefits of stakeholder mapping is that it really does give you a window into unintentional harms, and forces designers to confront all the ways in which they can positively help different constituencies and impact others.

One of the pitfalls is that it gets very hard to reconcile even a couple of opposing stakeholder interests. Reconciling a massive network of stakeholder interests would take a lifetime, so I guess the time it takes is one cost of this approach.

In design innovation it’s not practically possible to reconcile all stakeholders’ diverse interests. It’s an abstract ideal. The reality is that there will always be winners and losers in new technology. Change requires some burdens and benefits to be shifted around. Our job, in many ways, is to put the most ethical lens on that.

In this kind of systems-level work you have to be always optimizing, trying to find the most interesting, the most informative stakeholder examples to examine in depth, because in the reality of time constraints we’re just not going to get to explore all relationships fully. We tend to be constantly searching for where the strongest signal is.

As consultants, time is a luxury that we rarely have. We find ourselves constantly in this situation where we’ve got only a few weeks left to fully develop empathy for a diverse cast of internal and external stakeholders.

Apart from long-term thinking, ethics, and broad stakeholder mapping, perhaps the biggest new approach we are using is systems mapping and analysis. When we map out the causal loops that define an ecosystem, we can fully understand better where to intervene into that system in order to create the preferable change we seek.

Mapping a system is one challenge, but the spiraling complexity of systems can quickly become unwieldy, almost paralyzing: I have no idea where to intervene in this system to have the most effect. It’s difficult to stare at even moderately complex system maps and understand them fully. Time can actually be beneficial here, forcing us again to optimize how deep we go into thinking about a system’s secondary impacts or tertiary impacts, forcing us to come back to the primary deep structure of a system.

We’re aware of how tricky it is to get an understanding of where a system is right now, let alone what it will be like in the future. What will our system look like after we have intervened? This is a level that we haven’t yet be able to get to in our work, although we aspire to get there, perhaps by using simulation and modeling techniques.

Mitigating harm and maximizing benefits

Carlos: What influenced you to frame ‘responsible design’ as the next paradigm for Artefact?

Rob: It’s definitely not a new term and we also claim no proprietary ownership of it. Really our company perspective is that the tech industry, including designers, is not producing responsible outputs. I put this mostly down to a lack of tools and methods and inability to think through what we’re doing at speed rather than bad intentions.

There are two areas of responsible design that we think about: there’s the problem solving activities space and then there’s the delivery, or solutions, space.

Doing outcomes-focused work, mapping systems, having broad ethical conversations and reconciling stakeholders are all methods in the problem solving activities space.

On the delivery solutions side, becoming expert practitioners in how to design for accessibility and inclusion is just one example of how we can deliver to market more responsible products and services.

It’s important to say that striving to design more responsibly is not a replacement to legislative methods of controlling the impacts of technology. But curtailing bad actors and the negative consequences of ill-considered products and services should not be the work of governments alone. Designing responsibly shouldn’t feel like a burden to designers in these companies.

We have to remind ourselves that it is always in an organization’s best interest to do as much as possible to mitigate future harm and maximize the positive benefits of our work.

Register for Design Intersections 2019 to continue the conversation about activism, entrepreneurship, and leadership for large-scale impact with leaders from across industries and sectors.