Putting the “BIPoC” in Nature

By Latrina Lee

December 5, 2022

This article can also be read at Medium.com.

The Forest Preserves of Cook County (FPCC) has over 70,000 acres of land spread across the Cook County region. And 69,743 acres of that land (99.6 percent!) requires a vehicle or hours-long commute on public transit to visit.

This means that much of the FPCC remains inaccessible to the communities that would benefit most from it. On Chicago’s South Side, the Dan Ryan Woods is the only forest preserve site within a reasonable distance of public transportation. In a city like Chicago, this matters. Black commuters use public transit at nearly double that of other racial groups.

In 2020, the Forest Preserves of Cook County expressed its commitment to making the forest preserves more accessible and inclusive for BIPOC people. The FPCC approached the Fall 2022 cohort of the Institute of Design’s Co-Designing Social Interventions Workshop with three goals for increasing Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) visitorship to the forest preserves and its resources.

FPCC wanted to increase BIPOC:

- volunteers,

- usage of golf courses, and

- usage of Sauk hiking trails.

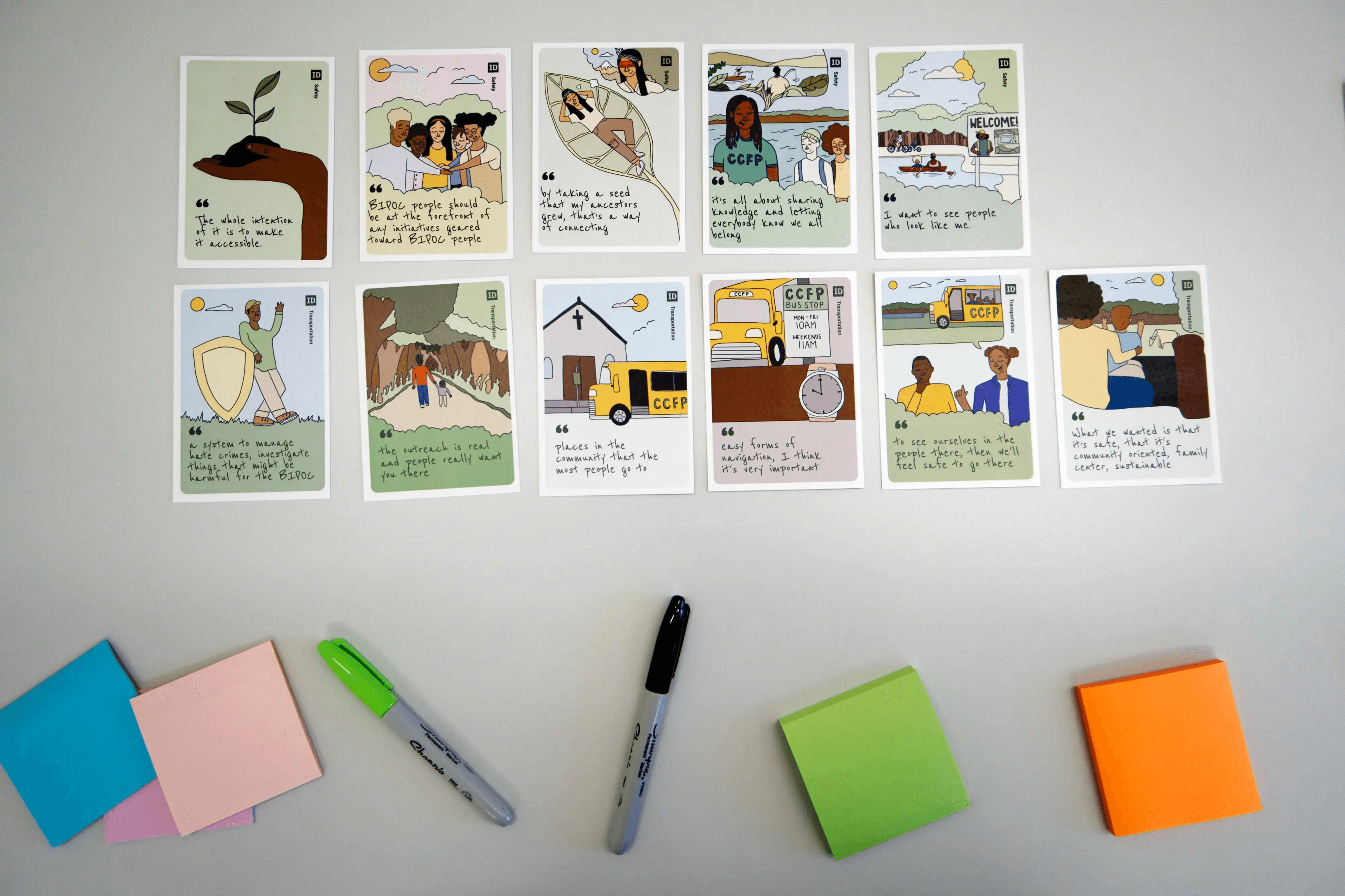

Under the guidance of faculty member Chris Rudd, founder of anti-racist design firm ChiByDesign, and Andre Nogueira, co-founder of Harvard’s D-Lab, the Institute of Design’s Co-Designing Social Interventions Workshop took a ten-month deep dive into the relationship between BIPOC people and the natural world. To design a strategy for helping the FPCC achieve its goals, we had to uncover the root of the problem: Why don’t BIPOC people utilize the resources the FPCC has to offer? The FPCC website lists 21 activities for Cook County residents to participate in while visiting the preserves; surely there is something for everyone to enjoy, right?

People without access to green space in their neighborhoods—a state called nature deprivation that is all too common among Black urban dwellers—are more likely to face depression, obesity, and heart-related illnesses. The University of Chicago Medicine, a healthcare provider for residents on Chicago’s South Side, completed a community health needs assessment in June 2022. The assessment documents that many people in the surrounding communities are disproportionately burdened with these same conditions. The increased risk of disease is not the only negative effect of a lack of access to green space. As one member of the community notes in the assessment: “Mental health problems are everywhere, but nobody talks about it because they don’t know how to talk about it.”

Many of us have experienced nature deprivation and might not know it. Think back to 2020—did you live in a densely populated city? Did your “yard” consist of a sad excuse for a patio or a small patch of grass littered with children’s toys? Did you jump at the chance to visit your friends with the pool or visit your mom with the hammock under your favorite tree? Did you miss the outdoors?

At the height of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders, many people in urban areas around the United States lost access to natural spaces. They gained first-hand experience of the effects of nature deprivation on physical and mental well-being. The New York Times published an article, “‘Nature Deficit Disorder’ Is Really a Thing” by Meg St-Esprit McKivigan, about the effects of nature deprivation on children’s behavior. McKivigan shares a Brooklyn mother’s struggle with providing her children with access to natural spaces during New York City’s stay-at-home orders. The mother noticed a significant change in her two children; they grew increasingly moody and cranky as the family isolated in their Brooklyn apartment, which lacked access to natural space. She considered renting a house with a yard for a week so her children had a place to play, noting her eight-year-old was jealous of his classmates with a yard.

The Journal of Pediatric Nursing published a review of literature, “Does Access to Green Space Impact the Mental Well-being of Children: A Systematic Review,” proving that access to natural areas can improve one’s mental well-being. Rachel McCormick, MSN, found that learning and playing in natural habitats reduces stress, improves focus, and builds confidence in school-aged children. Scientific Reports published an article in April 2021, “Associations between green/blue spaces and mental health across 18 countries,” which found living, recreating, and feeling psychologically connected to the natural world increased mental well-being in adults. Adverse impacts on health are not the only implications of reduced access to green space; what’s also alarming is the alienation and the lack of belonging BIPOC people feel when they do have access to natural spaces. BIPOC people feel unwelcome and unsafe when visiting natural spaces. Why?

In 2018, while renting a picnic area, a woman was harassed for wearing a shirt with a Puerto Rican flag. In the video, a white man berates a Puerto Rican woman, questioning her citizenship and demanding that she not wear the shirt “while in the United States.” The Forest Preserve police stood by as it happened. In a public call to action, the woman asks, “why my safety, no, my life, had such little value,” in the moments after the officer arrived and refused to take action against the man. Like many other BIPOC people across the US, she realized at that moment that access to green space is a privilege that BIPOC people haven’t been afforded.

In 2020, a Black birdwatcher in New York City’s Central Park asked a white woman to leash her dog, per park rules. The situation quickly escalated as the woman called the police on the man. He, meanwhile, stood behind the camera, recording her call with 911 dispatchers. Moments before the call, she threatens him by suggesting she will tell dispatchers, “there’s an African American man threatening my life,” which she later does. In the video, the woman grows increasingly animated as she lies to dispatchers and requests police immediately. In an interview following the incident, the man says the perpetrator intentionally tapped into a deep dark vein of racism that runs through this country. Her actions throughout the video were indicative of many instances we’ve seen before where people of color are perceived as a threat.

These are a few of the numerous instances that cause BIPOC people to feel unwelcome and unsafe in natural settings. When attempting to enjoy these spaces, there is the potential risk of racist interactions with people who make you feel you don’t belong. The students in the ID workshop—myself included—began to scratch the surface of the issue, and we found that belonging, or inclusion, was a central theme. We found it was much less superficial than BIPOC communities simply not engaging with golf, hiking, or volunteering. In fact, by picking at the invisible head of the issue, we uncovered centuries of systemic oppression; an infection oozing from deep within the folds our country.

The project took a turn down a new road. What happened, why, and how can we help fix it? Designers bathe in this friction. Tackling the complexities of intersecting challenges has become a part of the job description; we dive head first into ambiguity to “unstick” the sticking points. But how do we do this when the problem is only the tip of the iceberg?

Co-Design (Verb): an approach to design with, not for people.

The lack of access to green spaces among BIPOC people was a wicked problem if there ever was one. News flash to us designers in the room: we can’t solve wicked problems on our own. There are often factors at play that we sometimes can not see or understand. Co-design is the intentional involvement of the people most affected by the design. These are the people who have experienced exclusion and injustice; they are the ones that know what it takes to begin to undo the harm that has been perpetuated on BIPOC communities. Co-design empowers community members to tell their stories and address the root cause of the issues they face.

Safety (Noun): the condition of being protected from or unlikely to cause danger, risk, or injury.

In the first co-design workshop, the BIPOC co-designers discussed the definition of safety from the BIPOC perspective. We discovered from the co-designers that safety was fluid and ever-changing. At any point in one’s life, safety might look and feel different. One participant noted, “Safety is like a warm blanket just out of the dryer; it is comforting.” Another added, “When I was young, I would have said safety was visiting my grandmother’s house. I felt protected and seen. She made sure I had what I needed; I love visiting my grandmother.”

This insight sparked an eye-opening conversation for us designers in the room. Safety meant more than being safe from harm. People should also feel comfort and at ease when visiting the Forest Preserves of Cook County. To create a “safe” green space for BIPOC residents, FPCC must create a welcoming environment that allows BIPOC visitors to feel relaxed and welcome. We learned from the BIPOC co-designers that a part of the BIPOC experience is finding and creating safety in a world that is inherently unsafe and unwelcoming to you. The history of racism against BIPOC people is deeply rooted in the fabric of our nation; no wonder BIPOC people don’t feel welcome in places that not only display but also celebrate our nation’s dark past.

The BIPOC co-designers urged us, “don’t reinvent the wheel; utilize the resources in our communities.” The strategies we recommended for the FPCC to build anti-racist pathways to nature inclusion looked far different from the FPCC’s original intent. BIPOC community members led us to the realization that FPCC must address safety in the forest preserves before Black, Indigenous, people of color feel comfortable playing golf or hiking forest preserve trails. If BIPOC people don’t feel safe or welcome, should we expect them to be interested in participating? Would you?

Throughout the series of co-design workshops with BIPOC community members, the design team discovered:

- If BIPOC people don’t feel prepared, they won’t participate. Some outdoor activities require up-front costs that people are not willing or able to pay; many co-designers prefer participating in low-cost sports.

- The journey is long and hard; BIPOC communities have been systematically excluded from natural spaces. In Cook County, much of the land is inaccessible to BIPOC communities.

- BIPOC people don’t feel safe visiting forest preserves; the co-designers referenced racist incidents that cause BIPOC people to fear for their safety when trying to access natural spaces. These insights from our BIPOC partners shifted the course of the project; we now understood the root of the problem. We now need to materialize the FPCC commitment’s into actionable strategies and principles to increase BIPOC visitorship across the FPCC network of forest preserves.

Our final recommendation to the Forest Preserves of Cook County for creating an equitable and inclusive network of natural space was to develop partnerships with the people who understood the gravity of the situation most: BIPOC Chicagoans.

The strategies require that the FPCC:

- empower BIPOC visitors to cultivate a relationship with natural spaces,

- authentically welcome BIPOC visitors, and

- draw upon existing institutions and networks in BIPOC communities to engage BIPOC residents in environments that make them feel safe.

The thread throughout our recommendations focuses on the inclusion of BIPOC people. The Forest Preserves of Cook County must create an equitable and inclusive environment that welcomes BIPOC visitors and fosters belonging.

Without co-design, this project likely would have had entirely different outcomes. Our co-design approach enabled us to discover cultural nuances that help us designers begin to understand the BIPOC experience and design interventions that directly address the root of issues that BIPOC people face when accessing natural spaces. Ultimately, our nation’s systematic exclusion of BIPOC people from natural areas has contributed to higher rates of chronic disease, depression, and a reduced sense of safety in natural spaces. Co-design helped us address legacies of injustice and create equitable solutions for the future. As human-centered designers, we must remove the veil of injustice and advocate for inclusive design practices.

So what does this mean, and why does it matter? The areas of Cook County with high rates of chronic disease and mental health problems also happen to be the most nature deprived. As human-centered designers, we must design with the communities we have traditionally designed for. By using co-design practices to empower people to participate in the design process, we surface cultural nuances that inform the final design, ultimately making it more viable and culturally-inclusive. For some, having access to green space means having the ability to participate in their favorite hobbies such as birdwatching, golfing, and hiking. By working with BIPOC co-designers, we discovered the intangible levers that we must shift to help BIPOC people feel a sense of belonging in nature.

Lack of diversity in natural spaces cannot be reduced to lack of interest. For BIPOC people, nature is healing both mentally and physically. Chevon Linear and Kameron Stanton, the couple behind the BlackPeopleOutside TikTok account, share their nature adventures with their 65,000 followers. Both Linear and Stanton grew up the West Englewood neighborhood in Chicago; both feel that spending time outside is a powerful tool for both mental and physical wellness. In an interview with Pascal Sabine for Block Club Chicago, Linear shares, “We get to center ourselves around nature. We get to relax. We get to meditate. We get to become one with the world again and kind of get back into ourselves, and it’s super important to have a really good mental mindset right now.”

Everyone deserves that experience.

Tags:

Students

- Elizabeth Graff

- Emery Donovan

- Latrina Lee

- Luce James

- Sunaina Kuhn

- Yonghak Kim

- Ron Martin

- Takayuki Kato

Faculty

- Christopher Rudd