Where Must Design Go Next?

By Jarrett Fuller

March 22, 2023

If design is a form of cultural invention, then the history and future of design are deeply connected to larger cultural and societal forces. As we look to the future of design, ID dean Anijo Mathew identifies three forces that will drive design to evolve yet again: distributed trust networks, artificial intelligence, and conscious actioning. Design — in all its forms — must grapple with these issues and work with others across a range of disciplines to imagine new futures. How, then, do you design design? What is the future of design practice? How do you set up academic institutions to thrive under rapid change? What can we learn from design history to point toward a better future?

In this wide-ranging conversation, Anijo looks back at the history of ID (which, of course, is also the history of design) and paints what I think is an optimistic and encouraging picture of where design — both design education and design practice — might be heading next.

Students gather in front of the entrance to The New Bauhaus, Chicago (Herbert Matter, 1937)

JF— You were recently appointed the new dean of the Institute of Design. Can you tell me a little bit about how you see your role and what you want to do as dean?

AM— Being the dean of the Institute of Design is both a privilege and an honor, but it’s also a little bit scary because I’m standing on the shoulders of giants who came before me. Former directors have had films made about them and books written about them so it’s a little intimidating but it’s super exciting for me because I feel that one of the big things that I inherited is the transitions that the Institute of Design has gone through over time. One way to think about these transitions is to think about the changes that the design field has had over the last few years. ID is symbolic of those transitions. I am in the fourth era of the Institute of Design and I like to call it an era in process because I’m not a hundred percent sure what to call it yet. In order to understand this era, we need to understand the three preceding eras that came before it.

The first era was that of experimentation. As you may know, the Institute of Design was founded as The New Bauhaus by the Hungarian immigrant László Moholy-Nagy and was the direct descendant of the Bauhaus in Germany. His driving factor for the Institute of Design, or the New Bauhaus at that time, was that the Industrial Revolution was making things incredibly cheap and accessible. Products were becoming accessible to a lot of people, yet the production had this robotic, mundane aspect to it. What he wanted The New Bauhaus to do was to bring a little bit of craft, a little bit of design, into that production value. This was the birth of modernism. So a lot of the ideas came from Europe, from Switzerland, from Germany, and that translated into an era of experimentation at ID.

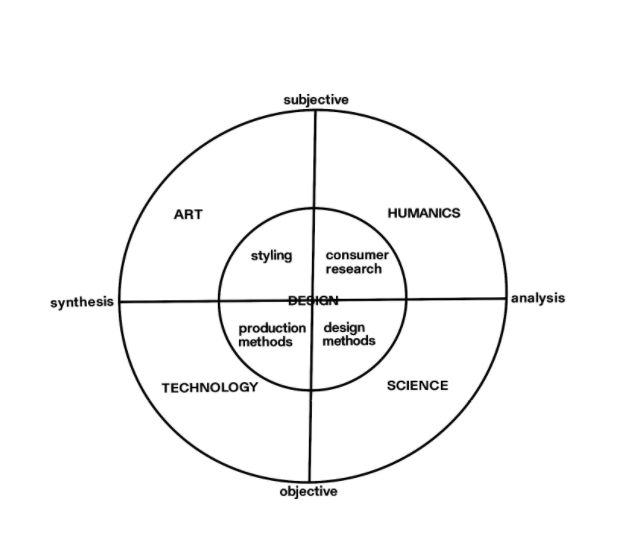

In the 1950s, a new director, Jay Doblin, came in. Doblin brought in the idea that it is not just enough to be experimenting or prototyping, you also need to think of products and services from a systems level. This is the second era, where ID pioneered the concept of systems design. Doblin and the faculty members at that time were really good at creating these large system solutions to the problems of art of the time.

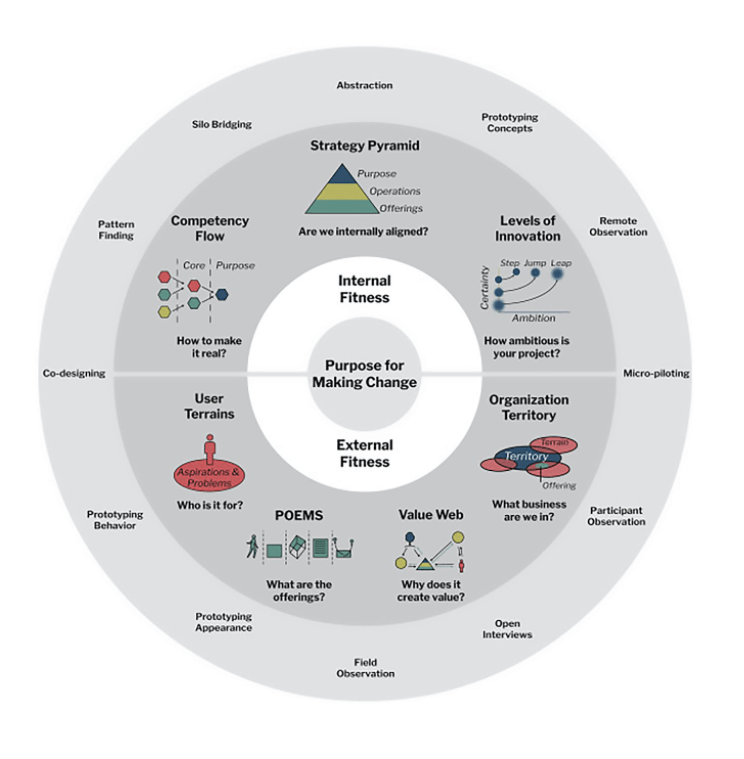

Then in the 1990s, another significant change happened at ID and this was the pioneering of the human-centered design era, or as we know it now, design thinking. Patrick Whitney and several faculty members here at ID said that it’s not enough to look at systems, we have to understand the users and the human beings that are in the system using these things. That allowed organizations to shift from shareholder points of view to human points of view. This was significant because you could make products or services that were making a profit for the company, but not really addressing the needs of the user. For many schools, as you know, this is the era that we are in.

What I am now leading is what we call the fourth era of ID. This is an era where it’s not just about the complexities of the systems, or the velocities required for production, but how to bring both of those things together. Say you are designing for public health or you’re designing new food systems, or you are employing generative AI, this is a completely different type of design. It’s designed around complexity and understanding a large number of stakeholders. Value exchanges are not easy. There are no easy transactions of value and you have to map all of that.

If I were to take a shot at defining this era, it is that we are now dealing with multi-generational change. We are dealing with things that will not just affect one generation, but multiple generations in the future. If you designed a bottle — let’s say a smart water bottle — the impact of that design is probably going to be felt by one generation of users. But if you design a health system for India, the impact of that is going to be felt by multiple generations of users. This is where design is playing a role and this is where ID is moving. This is the kind of thing all design should be focused on in the future.

JF— A couple of years ago you wrote a piece on Medium called “Design+ The New Normal,” which, to me, is perhaps a way to start to articulate this new phase. Can you tell me what you mean by Design+?

AM— I think this new era of design, which I like to call Design+, is going to pull from human-centered design, which uses principles of systems design, which uses concepts of experimentation within it. The way it’s going to translate into our everyday lives is that these problems that we are facing are too complex to be solved by designers alone. One of the big changes that design education needs to go through is a release of the hubris that we can actually do it all. If you think about the standard design studio, it’s about an individual student learning how to become a designer. When I went through architecture school, the only thing that I heard was, “Oh, you know these great architects that came before you? One day you’re going to become one of those. And your goal through the studio is to figure out how to get to that point.”

The truth is most of us are never going to become a Rem Koolhaas, or a Yves Behar, or a Jony Ive, but we will have an impact on the world. The way we have impact in the world is by collaborating with other people who look very different from us. Design+ is the idea that design plus an allied field can actually create more value than design doing anything on its own. It is the combination of these fields coming together that allows us to solve complex problems. The concept is quite simple, right?

One of the things that both fields have to do, but designers in particular have to do, is release the hubris so that we create new mechanisms to collaborate with these fields. I believe that the next era of design is going to be the development of theories, frameworks, tools, and methods for this collaborative stance. It is the ability for designers to express to an allied field — let’s say computer science or public health or engineering — that this is what we bring to the table and this is what we ask of you. When we do that, you can actually come together in interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary ways to solve complex problems.

Doblin's Design Circle (1950-59)

JF— Something that I really liked in the piece on Medium is that designers should think like APIs. Can you tell me about this metaphor and why this is so helpful for you for this new era?

AM— An API is an application programmable interface. The easiest way to explain this is that when you have two software systems that talk to each other, each calls for certain data from the other without actually giving up all the data. The idea is that not all proprietary information is shared, but enough is shared that the other software system can take that information and translate it for its own use.

For example, let’s say you have a New York Times map on crime data. What the New York Times is doing is calling Google Maps and saying, “Hey, give me the map for New York or Manhattan and drop in these stories that we have of crime that happened in Manhattan into the map.” So Google Maps gives the New York Times the map data, the geolocation data, and the New York Times gives to Google Maps the data that they have in the form of stories and narratives. Together, then, they can come up with this visual representation of crime data in New York.

Whole View Perspective Patrick Whitney, 2020

Now, if you take that same idea and translate it into design, the API model means that designers have to understand what the linkages are when they connect with another allied field. You can’t just walk into a room and say, “Let’s collaborate.” When you do that, in most cases, what happens is that it’s a multidisciplinary collaboration. The disciplinary boundaries never really go away and the people just do what they were taught to do.

One of the things we want to get to is this concept where those disciplinary boundaries slowly disappear and we try to address the problem as a cohesive unit. In order to do that, you need to understand what the linkages are. You need to know how you can translate your disciplinary knowledge into that non-disciplinary person’s vocabulary. You need to have mechanisms by which you can parse that allied field’s vocabulary and parse that into design knowledge. You need to express values that eventually become outcomes that are expressed internally and externally. What that means is if you are not gaining anything from this relationship, you’re never going to go back to this relationship. You need to have outcomes that are expressed externally so that these two disciplines actually give birth to something bigger than if each of those disciplines tries to do it on their own.

JF— When I hear you talk about how designers need to think about the way that teams collaborate and about shared outcomes and values, I can’t help thinking about this through the lens of somebody who is leading an institution. Can you be a little meta for a second and tell me how you’re actually thinking about this in your role? Is being dean a type of design?

AM— One hundred percent. I use the same conceptual frameworks in the structure of my activities every day. Let me give you an example of this. The first thing that I did when I became dean was to reach out to the other deans in the university and say, “Design is a catalyst. It’s only when we work together can design actually lead to output. So what are some of the ways that we can work together?” We need to invest in the outward and build collaborations outside of our comfort zones so that we can actually get to the bigger multi-generational problems.

What’s really interesting for me is that the world has a better appreciation of what design can bring to the table thanks to things like design thinking, which you may or may not subscribe to. We definitely don’t at ID. We think design thinking is a reduction of the complexities of design, but it has enabled non-designers to understand the value of design. A big part of my job is to reach out to these organizations and these companies and say, “How can ID work with you?” This manifests in collaborations that probably wouldn’t have existed in previous times. The University of Chicago has established a Design Lab at ID to help with healthcare outcomes at the hospital at the University of Chicago. We have companies that are interested in prosthetics design reaching out to ID to help them think about generative design and human-centered approaches to creating these prosthetics. None of this is unique, but in the sense that it leads to this whole concept of complexity and velocity working together to create multi-generational change, that’s where it gets super exciting.

JF— What’s really interesting to me in everything you’ve been talking about so far is that technology is not central here. I don’t mean that to sound Luddite or that it’s not driven by technology but everything you are talking about is still driven by people, it’s driven by collaboration. Often when you hear people talk about the future of design, they’re talking about it through the lens of technology: How is artificial intelligence going to change design? How is virtual reality going to change design? Can you talk about the role of technology here and how that fits into this larger cultural shift in design that you’re talking about?

AM— To understand all of this, one must contextualize it. Without basing it on the technological revolution that we are in, none of this would be possible. The foundation of all of this is the technology that is driving it, but the role of the designer is not to romance the technology. That’s the role of the engineer or the software scientist. If we start romancing the technology, then there’s nobody thinking about how it’ll be applied in the real world. This is what I tell my students: It’s not our job to romance technology. It is our job to critique the technology in both positive and negative ways so that it can be applied in the context of human activity or humanity-centered activities, whether that be for sustainability, climate change, healthcare, public health, education, whatever it is. It is our job to do that. An engineer may not think about that but that’s not their job to think about that.

I believe that there are three seismic forces that are acting upon design that all designers should be conscious of. The first one is distributed trust. This notion that trust in institutions is eroding is something we should pay attention to. What that means is we already have technologies that question the foundational belief we have in financial institutions. Think of cryptocurrencies or blockchain. We have a group of people who are starting to question how public health can move away from hospitals to community-based care. What all of this is leading to is the emergence of a new type of network that is centered around distributed trust. That trust is not centered around one individual or one institution, but dispersed in the community, whether it be through blockchain, where we can certify that a certain action was done as a community or in the form of health outcomes or food systems that are governed by a group of people rather than an institution.

The second change is artificial intelligence. We saw the birth of some revolutionary ideas just in the last few months with ChatGPT and DALL-E 2 and Midjourney that are going to change the way we think about everything, including design. What are you going to do if DALL-E 2 can create a hundred options in ten seconds? What is the role of the designer then? Sam Altman, the founder of ChatGPT, says that it is the intersection of humans and technology that’s going to lead to the changes that he envisions through ChatGPT. It’s the interpretation of that data. It is the manipulation of that data. It’s the use of predictive analytics so we can say, “We have 1,000 options, but the only three that work in the context of rural Africa are these three because we know inherently what the human system looks like.”

This leads to the third seismic change that’s happening: conscious actioning. As a society, we are now holding our leaders to a higher standard of action than ever before in human history. We are asking them to be more judicious about the decisions that they’re making in thinking about race, ethnicity, health, and climate change. It’s no longer about the individual anymore. It is about actions that are more conscious and will affect a larger group of people. Here, too, design is going to get impacted. The whole concept of human-centered revolved around the idea that individually, we are going to take charge of the values that are being transferred over to us and that individually we are going to ask for better values. Conscious actioning means that we are going to think beyond the individual to more community-based experiences, more humanity-based experiences. The notion of what value design brings to that conversation is bigger than human-centered design. It’s about co-design or engaging communities in the conversation. It’s about changing the value exchanges that come from shareholder value to stakeholder value. It’s about corporations understanding that this production of wealth and goods is not an outcome that is conducive to human development as a species.

I believe that in all three of these changes, design will play a major role in the future. The role of the design school is going to change from helping designers create widgets for apps to helping them be part of the team that writes executive orders at the White House. That’s the level of change that we are going to see in the next few years.

JF— What makes ID ID? I’m interested in how you think about ID as a brand and as an institution, as a thought leader, but also acknowledging that ID is filled with a bunch of individuals who have their own research agendas, their own interests, their own things that they’re bringing into the program, whether that’s faculty or students or administrators. What is that overlap between the individual and the institution?

AM— I think it’s really important to think about these things as an administrator of an entity that is filled with entrepreneurs. If you think of every individual faculty member, we encourage them to be their own entrepreneur. We encourage them to have free thought. I think this is something that we should nurture. Having interacted with education systems around the world, I have noticed one thing: The United States has something precious and that is the idea of academia being free to do what they want to do. This is somewhat unique to the US in the sense that faculty members are able to do what they want to do. It’s this notion of academic independence or experimentation.

This has nothing to do with tenure or all of the other procedural conversations that we have in universities now. That’s not what I’m talking about. What I’m talking about is this combination of freedom, entrepreneurship, the ability for a faculty member to say that I’m going to use my lab or my classroom as a sandbox to think about things that other people are not able to think about. This creates incredible value because it stretches our points of view beyond what capitalism can do. Capitalism can be a great driving force for change, but it is bound by the idea of economic development, or capital development, or shareholder value. Education — or academia — has the ability to think beyond that, to question some of the things that a capitalistic enterprise might do, to stretch or force or encourage that enterprise to think beyond what it’s doing right now. I think this is the ideal of the ID brand. The ID brand is this ability for us to be ahead of industry.

We are not a training ground for industry. The only way that we can do this is to bring a group of really interesting, crazy people who are willing to take risks and give them the freedom to do what they want to do within boundary conditions of ethics and education and knowledge creation and outcome-oriented structures that all knowledge must be free and open to everybody.

To me, this is how ID differentiates itself from other design schools. We have a group of faculty members who are encouraged to think about these multi-generational problems that other design schools may or may not be thinking about. It creates this platform, this sandbox approach, and tells the faculty members, “Hey, if you want funding for this, I’ll find you the funding. That’s my job to get you the money to do this radical thing. You don’t have to worry about that. If you want to do this without funding, that’s fine too.”

If a student body comes in and says, as they do at ID, that diversity is an important conversation to have and that diversity should be part of our core curriculum, we talk about that as a faculty. We don’t ignore the students and just say, “Hey, here’s what we have taught for the last twenty years and nothing’s going to change.” I think that’s the idea of ID that keeps me here. I didn’t go to ID. I’m not an ID graduate, but I love ID because of that idea.

JF— I want to underscore this idea that design school is not a training ground for industry, but is actually a playground to change industry. This speaks to everything we’ve talked about: All of these changes in design, they’re also correcting blind spots, making adjustments. They’re all working towards a better future. That’s what design school is for. It’s to change the industry.

AM— And the interesting thing is that this also leads to incredible career outcomes for our students. Because we are training them to take on leadership roles, they actually get into senior positions in companies. The average increase in salary is about 166% if you come to ID. Nearly three times. We have the highest median income range. Wall Street Journal tracked income ranges for design schools, and we have by far the highest median income range for any design school in the country. It also speaks to this kind of industry mindset. If you give them people to do the work, they will hire you and they’ll make you do work. If you give them people who can question the practices, they will hire you and ask you to question practices. Our job is to create conversation, to question, to critique. To say, “Hey, what if we brought artificial intelligence into supply chain management? What would that look like for our users?” That’s a different conversation from, how do you design a website for the user?