How Can Design Make the Biggest Impact?

By Jarrett Fuller

March 15, 2023

Over the last decade, there’s been an increasing awareness that design can and should not be exclusively employed to maximize profit. The tools of the designer can aid in making the world better whether that is toward a more equitable society or greater environmental sustainability. Design for social good is a growing area of design practice but it does not mean we leave corporate clients behind. What is the role of more traditional design practices within a socially conscious design field?

John Payne and Wesylnne Ashton, two designers and ID professors, are working at the forefront of these questions. Weslynne is an associate professor with joint appointments in ID and the Stuart School of Business. As a sustainable systems scientist, her research, teaching, and practice are oriented around transitioning socio-ecological systems towards sustainability and equity and her current work focuses on urban food systems and regenerative economies.

John, who joined the ID faculty in 2020, is the director of experience design at Verizon and serves as chair of the board of directors of the Public Policy Lab, a non-profit service design consultancy. A leader in human-centered interaction design, John’s work embodies this intersection of business and social good that interests many designers today.

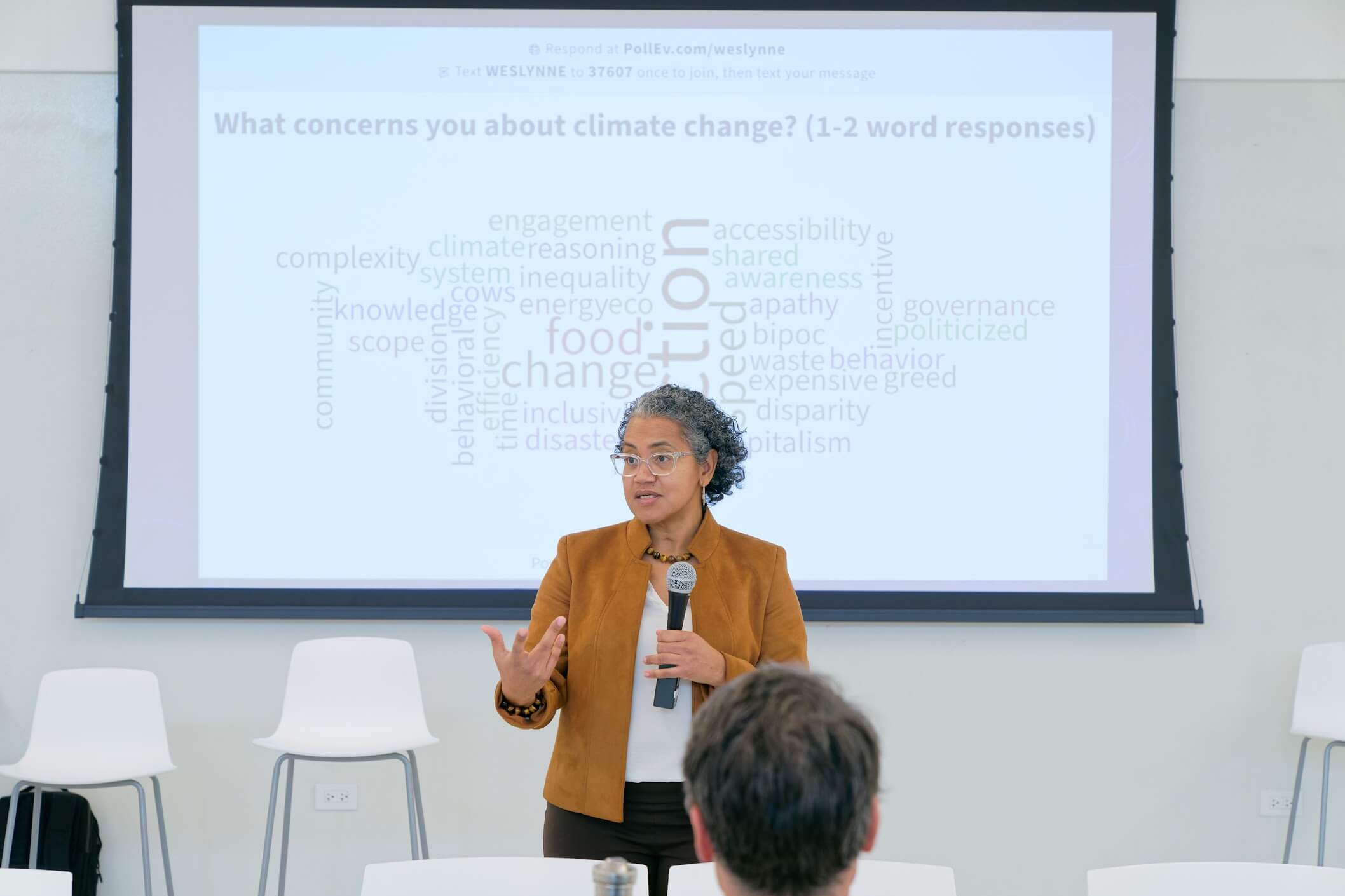

Weslynne Ashton presenting on climate change at the 2022 MDM Immersion session.

JF— Weslynne, I’d like to start with a question for you. Your background is not in design. You come from an environmental engineering/environmental science background. I’m wondering if you could talk about where design came into your work and how your background influences your perspective on design and the role of design.

WA— I started my career as an environmental engineer, and I would say that I’ve been practicing design without knowing that it was design for a long time.

In my final semester of undergraduate, I took a course called The Politics of Sustainable Development and I was introduced to the concept of industrial ecology, which is how we design our industrial systems so that they might be more ecological and operate in harmony with nature. I loved this concept because up until that point, the work that I had been doing was all about understanding the environmental impacts of various activities like how to clean up a lot of the pollution that we had created. Then here’s this concept that says, “All right, let’s not just clean up the pollution, but let’s think about how we can design out the pollution from the get-go.”

For graduate school, I chose a program in industrial ecology with this design mindset without having any of the design tools. I really didn’t formally get introduced to design until several years into my position at Illinois Tech. We have this interprofessional projects program at the undergraduate level that all of our undergraduates have to take, and about two years into being an assistant professor here, I was invited to participate in what was called the IPRO 2.0, which was trying to bring in more design tools into the IPRO led by Jeremy Alexis along with five or six faculty from across the institution who were trained in design thinking as a part of this IPRO redevelopment process.

That was my first foray into formal design tools and I take little snippets here and there and try to inject them into my classes. I officially joined ID in the fall of 2020 after some more in-depth interaction with faculty and students.

JF— John, you’re the director of Service Design at Verizon and then you’re also the chair of the Public Policy Lab where you’ve done a lot of work around designing for healthcare. How does that relate to work at Verizon and vice versa? How do you see these things fitting together?

JP— Service design is the thread between the two roles that I currently hold as chair of the board at Public Policy Lab and as head of service design at Verizon. Service design is a practice that allows a group of people to engage with both the design artifacts, the events around those artifacts, and the outcomes in peer-based ways when facilitated as a practice.

The Public Policy Lab is a nonprofit service design consultancy that works exclusively with government agencies, philanthropies, and research institutions to develop human-centered strategies for social innovation. In particular, they focus on developing policies and services through the research, designing, and testing phases. Bringing service design into that realm is a fairly new construct. It’s not the typical way that government agencies do this work.

At Verizon, service design is also a fairly new discipline. It’s housed within a much larger design organization that is much more well-established but over the past four years or so, we’ve introduced service design approaches to address the deeply complex problems that telecom faces when interacting with their customer base, which for Verizon, is about a third of the country. So there’s a significant amount of complexity in interacting with that broad set of people.

None of our favorite interactions are customer service interactions with a telecom company, so it’s actually a really wonderful laboratory for bringing service practices into the organization because there’s so much coordination that is required.

JF— It would be really easy to see those as two very different goals, very different activities. When I talk with younger people interested in design, they are frustrated with the big corporations that are governing so much of our lives and the profit motive that we see. I’m not asking you to speak for Verizon, but comparing a for-profit company versus a nonprofit, does service design mean different things? Do the goals of for-profit and nonprofit organizations overlap at all?

JP— While the process is the same, it’s actually having very different impacts on the two simply because of the way the organizations are structured. Verizon’s essentially a laboratory for how to do this at a significant scale while the Public Policy Lab is a small nonprofit consultancy doubling down on the true nature of human-centered service design, in that it’s about bringing the public into the process and allowing them a voice through policy creation and public service creation processes where they didn’t have a voice in the past. It’s about representing the needs and desires and lives of the public — in particular, at-risk and underrepresented communities — in the design process.

At Verizon, it has useful effects on the consumer experience, so that’s the baseline. But the effect it’s having within the organization is a unifying effect where the different groups from our technology organization, from our product management organization, from a marketing organization, as well as our customer experience organization, which I’m a part of, all have roles to play in how an experience of a consumer unfolds. The choreography lends itself to allowing teams to see where their roles manifest, how those touchpoints reach out to the customer, and how those interactions with a customer all need to coordinate with each other. The practice of the work helps to unify the approach of the organization in producing services.

JF— Weslynne, you said that you were doing design before you realized it was design. Can you talk more about that? How do you see the role of the designer in these big complex problems?

WA— I come from a systems design perspective: How do we understand the current systems that we’re operating in? What are their goals? Who are the key stakeholders? What are their interactions? What are the feedback mechanisms? What are the opportunities for change? I think designers have an important role to help show the system, and these relationships, and really visualize that in a way that people can see and relate to.

It’s also about visioning and thinking about how we can create new visions of the future through prototyping, looking at changes that can be made at various scales, making those changes, learning from them, and adapting. Designers also have an important role in facilitating, convening, and bringing different groups of people together to help bring about a better understanding of systems, creating plural visions of the future, and pathways to help get there.

One of the courses that I teach right now at ID is around design for a change in climate. What are the fundamental things that designers need to know about climate change? Then can the set of skills and way of working that designers have be applied to climate change, either within a private company, or within a government agency, or a broader system? So we’re playing around with different types of tools to help build design capacity for climate change as well as applying design tools to address climate challenges.

JF— I’m wondering if these processes, these ways of working, need to be done by designers? Are you primarily teaching people who will be self-identifying as designers or do these tools and methodologies have a context where there might be no designer presence?

WA— I have a multi-level answer to that. I sit in a joint appointment between design and the Stuart School of Business. I’m teaching business school students on one hand and design students on the other. On the ID side, I try to expose designers to broader systems thinking, environmental, and social issues. Basically, how do we measure the impacts and then develop design tools to mitigate those impacts? On the business side, it is also exposing them to sustainability issues, but also design thinking and the role of design in there.

Then through various projects that I have been working on mostly in Chicago, there has been a concerted effort to bridge design practice and share those design skills with our partners, through a co-design approach: recognizing that we can build design capacity, mindsets, skills, and particular tools with partners.

JF— I see people talking a lot about wanting to make everyone a designer and make these design tools available. There’s a push to be multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary until you get into the project itself and things become very territorial. How do you think about the organization of teams and the role of design in these complex problems?

JP— In Kevin Slavin’s article “Design as Participation,” he writes, “Designers of complex adaptive systems are not strictly designing systems themselves. They’re hinting those systems towards anticipated outcomes from an array of interrelated systems.” I start with that quote because that’s a framing mechanism that I use in both spheres. In the Public Policy Lab, any introduction of a new public service or a revision to a public service exists in a very complex existing ecosystem and our ability as designers. We are participants in a complex system and we’re able to change parts of it, introduce new stimuli, and hopefully move things towards. Then at Verizon, there’s a lot of it on the inside of the organization in how we reveal to the consumer the coordination of our experiences. I’d say the role of the designer in both instances has a strong facilitation component. The mindset of the designer is one where we are going to get together and create something as opposed to deciding on something.

WA— I think that mindset is really important. It speaks to how we are training designers to show up. Are we training them to show up as the experts with particular skills, or as participants and facilitators on equal footing? I think the recognition that everyone can create and has that potential is so important but we don’t necessarily have the skills and opportunity to do it. Particularly, when we think about under-resourced communities, both in the US and abroad, there’s a dearth of opportunities for people to exercise that creativity, which is not to say that it doesn’t happen. There are breakthrough cases of people who, despite whatever their circumstances, are able to come up with new inventions and escape from wherever they are with innovations but maybe we need to start that training for creativity a lot earlier in life. Do we need to be teaching design thinking to elementary schools?

JF— It’s a cliche at this point that design is problem-solving. Yes, design is problem-solving, but that’s actually just a very small part of it. It’s sort of the hammer and nail situation where if you keep telling yourself that design is problem-solving then everything can be solved with design. What I love about what both of you are saying is that the solution is much more complex — if there even is a solution — it’s much more interdisciplinary. Design’s role is not actually in the solving but in the invention, it is in the platform creation. This idea of design as platform creator or design as, I don’t know, cultural inventor seems much more generative and generous than design as hero.

JP— I couldn’t agree more. I’ve been a designer long enough to have been at the beginnings of the introduction of human-centered design as a practice and now it is really the primary expression of design and problem-solving at the center of that. That enabled the practice of design to be more widely adopted — which is wonderful — but to your point, it’s also quite limiting. We are not caring for the other side of it that you described as design as cultural invention. There are many disciplines that solve problems. There are many fewer disciplines that create cultural artifacts, processes, services, events. Design isn’t the only one that does that, but that side of our practice needs to be recognized and talked about and brought to the fore.

JF— What are the skills or the ideas or the methods that we could be teaching designers to be thinking more expansively about when they are injecting themselves or being asked to be a part of these larger multi-disciplinary teams?

WA— The entry point for most designers, working either in the public or private sector, is that you are issued a problem to solve. Often, there’s a scope of work, a brief that sets the parameters of the understanding of what the challenge is. There’s a certain number of hours that you’re expected to spend working on that project. But it takes much more than that to really be able to understand the systemic challenge.

So in a way, a designer has to make the case for why the organization should take a more systems-based approach and try to tackle something that’s bigger than what they got in the design brief. We talk about using design to better understand the problem and reframe the problem for your clients or whomever you’re working with but I think it’s also important to understand the intervention points and the opportunities for leverage. There are times when all you might be able to do is try to reduce the service time or the amount of time spent on dealing with a particular problem and there may be other opportunities where you can also show opportunties for making a larger change.

JP— One of the things that I’m working on in my classes is developing methodologies for developing more cultural and social sensitivity around the impact that the things we put into the world could have. We can’t ever guarantee or predict the impacts things will have. Clearly, the designers who created the Facebook interface probably didn’t ever consider the effect it might have on American political life. The designers of Uber probably didn’t think far enough ahead to imagine its participation in labor practices around the world. Our practices are excellent at designing individual and small group interactions with a product or service but we don’t, as a design practice, have very many robust methodologies for thinking about and developing ways to make decisions and be intentional about the impacts that our work might have.

JF— ID, historically, has been very business-focused. It was very connected to industry. But I currently see a lot of excitement and focus — both at ID and design at large — around civic design. This doesn’t mean we just completely stop designing for industry. Could you talk about the relationship between business and civics and this move towards working on systemic cultural or societal problems?

JP— I’m a graduate of ID from the era you speak of where it was very business-focused. I am an industrial designer by training and being introduced to design at ID and how it applies to business in the early days of human-centered design and design thinking was quite refreshing. I really love designing things too, but the idea that design could be applied to something as abstract as a business model was fascinating.

I see this as concentric circles radiating out from the well-established to more analogous types of things in the civic space. It’s an easy bridge from design thinking for corporate life, to thinking about design thinking for government, for example. Then there’s the more complex wicked problem space of social problems, of potential cultural impacts of, say, climate change. To me, it seems like a logical progression and it’s an exciting one, just the way I felt early on when I discovered and started to practice design in the business space.

WA— Anijo Mathew, who’s the Dean of ID, talks about this 85-year history in eras. In each era, we don’t leave things behind but we’re building upon them. We expect to continue to work with industry and to use human-centered design tools, but we’re in a yet unnamed era of design, that is more civic engaged, that is thinking about how we tackle these bigger problems.

On many levels, people are looking for more purpose. Organizations are also grappling with their purpose and how to live up to that purpose. It’s not just about being the most profitable. How do you be profitable while serving a bigger purpose? Purpose, I think, needs to be the North Star. What are we working towards? There are going to be roles that business will maintain and roles for the public sector and there are going to be collaborations across the two.

We’re going to see more and more people going throughout their careers between the public and private sectors, and that line is really blurred. There’s definitely still space and opportunities for our work to be valuable to industry — most of our students are going to look for jobs in the private sector — but more and more, there are opportunities in the public sector for them to connect to.