Maybe We Are Not Geniuses

By Elizabeth Graff (MDes 2024)

May 7, 2024

Jay Doblin is a name that few recognize outside the Institute of Design (ID). Yet, Doblin played a key role in professionalizing the field of design. Many of the curricular decisions he made during his tenure as Director at ID laid the foundation for how we practice design today, but in ways even he couldn’t possibly have imagined.

In my final semester of my MDes degree, I took the opportunity to reflect on the impact that Doblin had on ID during his tenure. Drawing on research conducted by ID alum Todd Cooke (MDes + MBA 2020), Kristin Gecan and I created a three-part series highlighting some of the most significant ways that Doblin changed the trajectory of the school—and the field of design.

In particular, we look at:

- The way Doblin built on Gestalt theory to reshape the school’s approach to visual education;

- How Doblin moved the school away from artistic experimentalism and toward rigorous methodologies; and

- Doblin’s role in shifting design’s focus from single products to complex systems.

Having completed this deep dive into Doblin’s impact on ID, I can’t help but wonder what Doblin would think of our school now, 75 years since he stepped into the role of Director. Would Doblin recognize his imprint on the methods we learn, the problems we tackle, and the work we produce today?

The Flushmobile

Doblin tasked students with projects that were equal parts challenging and congenial. One such assignment asked students to build a car powered by any form of cheap, readily available fuel, whether water, air, or electricity.

With the “Flushmobile,” as recounted in a student newspaper, a student “…got an old hot water heater filled with water and compressed air . . . so that the water squirted through a nozzle with a tiller to guide the propulsion system.

“It could get going roughly 30 miles an hour down State Street and would create this beautiful rooster tail . . . if the sun was shining, you’d get this gorgeous rainbow effect.”

Explore this and other elements of Jay Doblin’s story on Google Arts & Culture starting here.

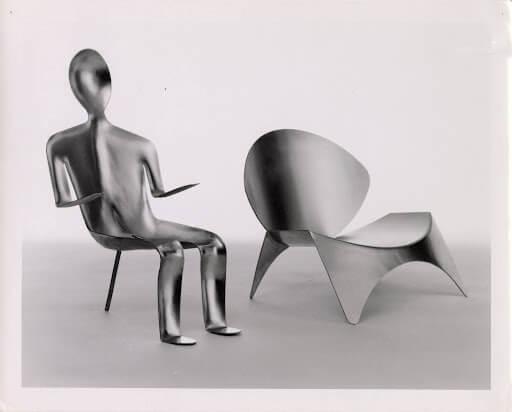

Aluminum Chairs for Alcoa

Under Doblin, the school became something of a magnet for corporate-backed innovation. Students benefitted from Doblin’s many contacts in the commercial industry, as high-profile American corporations invited them to solve actual problems.

One recurring contract was for Alcoa, the world’s eighth largest producer of aluminum. The brief asked students to design a chair using a single, standard sheet of square aluminum with minimal material waste.

Explore this and other elements of Jay Doblin’s story on Google Arts & Culture starting here.

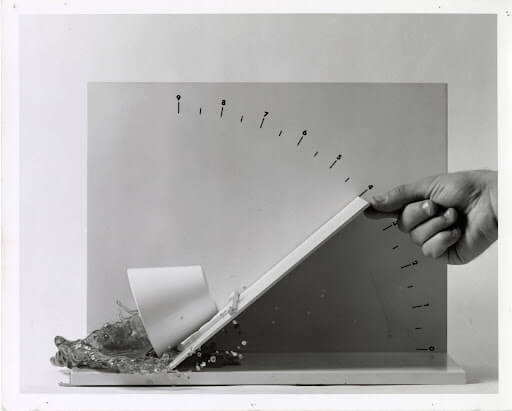

The Teacup Experiments

With little patience for what he called Moholy’s “diddling attitude,” where “every experiment led to four more experiments,” Doblin preferred measured, methodological experimentation.

Doblin’s experimentalism was largely based on the scientific method, in which an enduring constant was subjected to varied conditions. One exemplary project was the so-called teacup experiment, which Doblin conducted in collaboration with students over several decades.

Explore this and other elements of Jay Doblin’s story on Google Arts & Culture starting here.

In the 1950s and 1960s, under Doblin’s directorship, ID students designed cars and aluminum chairs. They literally studied the properties of tea cups!

In contrast, during the three years I spent at ID, I co-designed strategies to create safe experiences for BIPOC visitors in nature; used speculative design to imagine life in a post-climate change migrant community; and designed a service to nudge families toward climate-friendly diets.

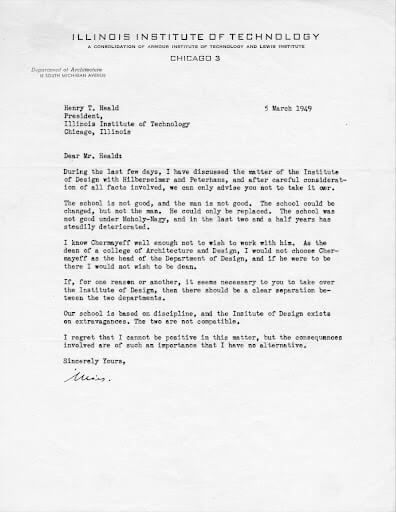

Jay Doblin became Director of ID in the middle of a fraught merger between ID and Illinois Tech (then known as IIT). Although ID and IIT’s College of Architecture were both intellectual descendants of the Bauhaus movement, they had taken the German tradition in different directions—while ID’s first Director, László Moholy-Nagy, embraced the artistic experimentalism of the Bauhaus, under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe the School of Architecture espoused the Bauhaus’s purism.

Doblin similarly described the schools as “diametrically opposite in educational concept.” Yet, unlike Mies, Doblin saw the rejoining of these two Bauhaus offspring as “an extraordinary opportunity that [he] could not pass up.” Doblin saw himself as an “interpreter” who could translate between ID and the School of Architecture, “bridge the gap,” and “reestablish a rational dialogue between the two.”

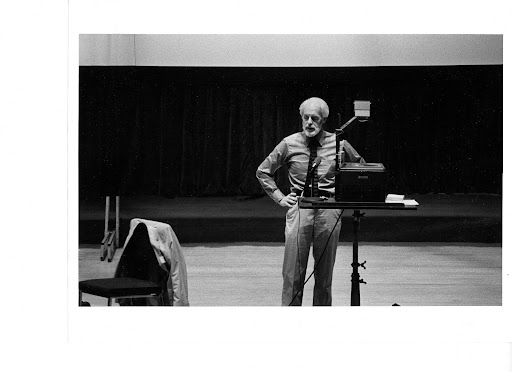

Yet the merger took place. And years later, on May 11, 1974, IIT hosted an all-day symposium to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the merging of the two schools. The event took place at 632 N. Dearborn—home of the Institute of Design at the time of the 1949 merger.

At the event, Doblin delivered a speech in which he reflected on his tenure as Director of ID:

I must confess that at that moment [i.e. the beginning of my tenure as Director] I felt more for purism than I did for experimentalism. I was awed by Mies and his work but quickly fell out of love with this narrow concept of education which I found stifling and arrogant… I knew that experimentalism was a powerful educational tool, but its very nature defeated finishing anything, inculcating a sort of “diddling” attitude which became an end in itself. Every experiment led to four more experiments.…[My] goal was to develop designers capable of constructing an informational base on which proper solutions could be made….to establish a school where serious research underpinned the design activity….We salvaged the best of experimental education (which had survived many changes since the Bauhaus) and added to it a carefully constructed program of information-based design that produced noncommercial products that worked. …Our aim was to produce designers who had the will, ability, and the ethical base to change American production for the better.

—Jay Doblin

Over my time at ID, I’ve come to appreciate the ways in which design is still wrestling with the tensions between the polarized extremes that Doblin sought to marry. We’re exposed to rigorous design methods, many of which were pioneered by Doblin and his colleagues. We practice these methods in order to get a feel for what types of information and insights each method can unlock. Through this practice, we learn that design is teachable and learnable; there aren’t design geniuses. Rather, there are people who know how to structure the design process effectively, how to select and combine design methods and convene the right stakeholders in ways that create the necessary “informational base” Doblin described.

I believe Doblin was right to push design toward methodologies; we need ways of contextualizing and framing challenges that aren’t based on instinct alone. The more that designers work on wicked problems and the more we collaborate with professionals in allied domains who need to trust that our conclusions are valid, the more important these practices become.

But design isn’t a hard science. After we dismantle the black box of the creative process, we need to find ways to preserve its magic. The lesson I’m currently learning is how to bring my intuition back in while still upholding the rigor I learned at ID. Knowing that our gut instincts are often wrong, how do we hold space in the design process for our full humanity and for the unique wisdom we each carry? How do we move through our work with genuine humility given all that we don’t know and also trust our inner voices at the same time? What posture do we take toward our intuition, knowing it can serve as a liability, but also as an asset? With experience, we learn to practice design in ways that are both grounded in theory and also authentically reflective of ourselves, and in so doing, further develop our creative confidence.

There are moments in the Foundation curriculum where Doblin’s assignments are still used today and countless other ways that his influence is woven into the cultural fabric of the institution. Yet, as the school and the field have continued to evolve, I wonder which aspects of design practice today would surprise him most.

Doblin believed that designers needed to expand their focus from products to systems. But did he know how far afield we would land? Did he ever envision us working in sustainability, healthcare, and food systems?

Doblin also took it upon himself to create an objective definition of “good” design. So how would he feel about classes like Politics of Design, Co-Design, and Designing Futures, in which we critique the intellectual foundations of design as “a view from nowhere” with the authority to create one objective standard of “good design” that holds up across cultures and contexts?

In advocating for replacing artistic intuition with a set of replicable, repeatable design methodologies, Doblin began the important process of democratizing design. He helped us move away from the idea of “designer as genius.” But I wonder how he would have felt about the idea of “designer as facilitator” or “designer as convener.” How would he have viewed processes that value (or even privilege) non-Western and feminist forms of knowing? Or practices that welcome non-designers into the design process as equals? I wonder what he would say about the approaches I learned about at ID that inspire me, such as data feminism, inclusive design, speculative design, crip futures, Afrofuturism, posthuman and multispecies design, and liberatory design.

Mostly, though, I look forward to seeing what the next 50 years will bring for our field and for ID. How will design continue to change as the world’s challenges become increasingly complex and interconnected? What do we believe about where design might go next? And what impossible-to-imagine evolutions are we laying the groundwork for today? I’m excited to see how our new dean, Anijo Mathew, articulates and refines his vision of “design as API,” one in which I can’t help but notice echoes of Doblin’s legacy as an interpreter and translator in his own right.

In May 2024, the Institute of Design celebrated its most recent graduates, It was 50 years—to the day—since Doblin’s speech. Check out our 2024 End of Year Show and you’ll get a peek into the future.