Building Connections to Native Culture Through Interactive Design

By Stephanie Hlywak

December 8, 2023

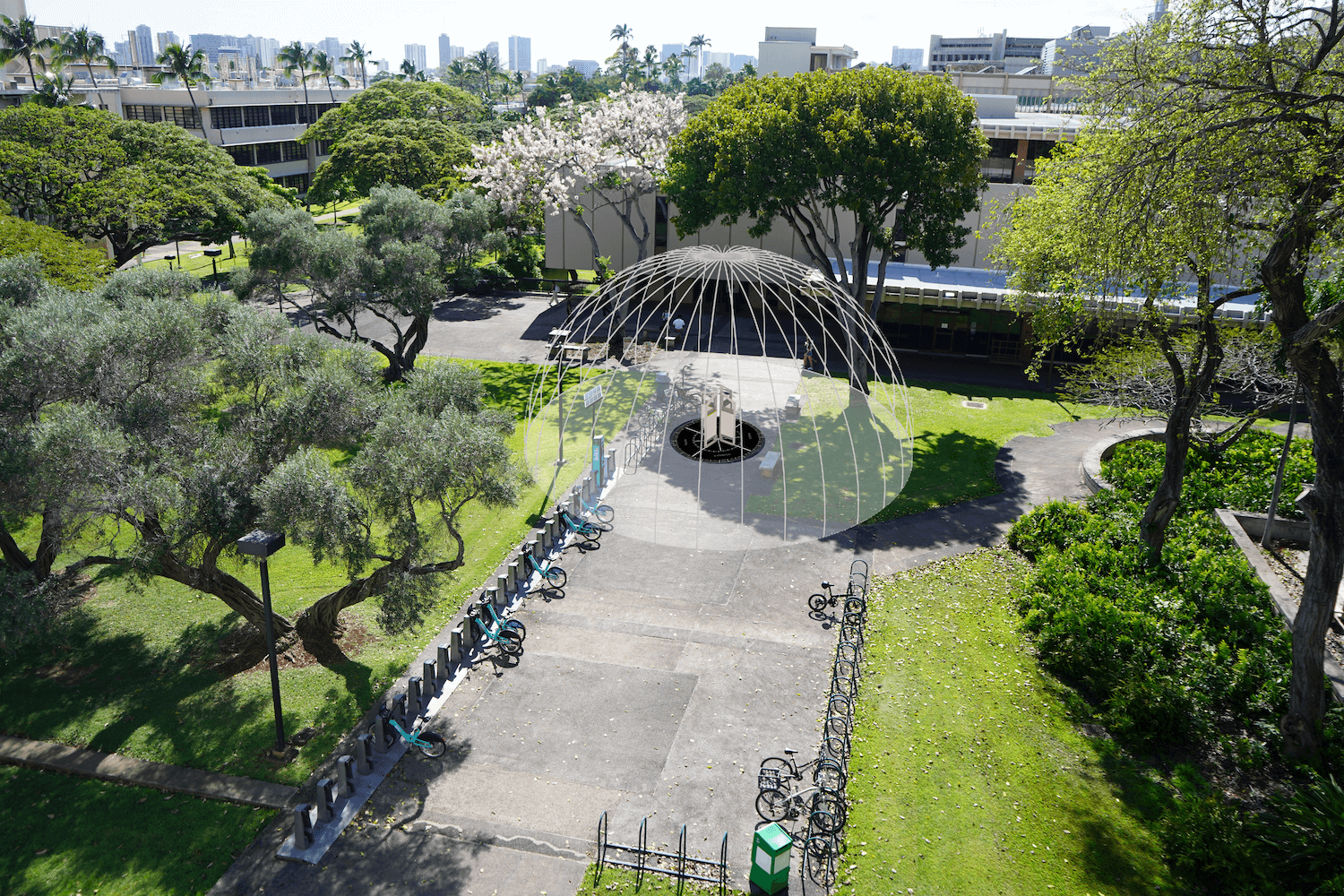

At the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (UH Mānoa), non-native Hawaiian students make up roughly 85 percent of the undergraduate student population. Its history, as an institution, is also deeply connected to the history of colonialism on the island; the university opened its doors less than 10 years after the United States annexed Hawaiʻi in 1898.

It’s an apt space, then, to explore ways of connecting traditional knowledge with modern realities. For non-native students at the University, the history of colonialism and Hawaiian concepts of land, community, and time are not the primary focus of their studies.

Can we seamlessly integrate these concepts in a gamified way to elicit students’ interest in the significance of Native Hawaiian culture? Two Interaction Design directions suggest the answer is yes.

Respectful Design

In an effort to honor the indigenous history of Hawaiʻi, The University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Brian Strawn (MDes 2012), Director of the University of Hawai’i Office of Planning and Spatial Experience and Principal Investigator for the project through the University of Hawai’i Community Design Center, partnered with students in ID’s* Spring 2023 Communication Design Workshop to create informational prototypes that make visible the island’s indigenous land division system, along with other spatial concepts, in ways that current students and community members can easily understand. ID students studying with Professor Tomoko Ichikawa were tasked with translating complex, culturally ingrained concepts into accessible technology.

But introducing indigenous ways of knowing into our current reality requires a decolonizing design process. Brazilian researcher and member of the Decolonising Design Collective, Pedro JS Vieira de Oliveira PhD, defines decolonizing design as “the deconstruction of the Anglocentric and Eurocentric thinking when it comes to the practice and the design by itself.” At a recent conference, Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD) University’s Dean of Design, Dori Tunstall, suggested the ethos of Respectful Design as a method of achieving that decolonization. Respectful design, she said, acknowledges the power dynamics, potential harms, and tensions in designing while valuing other ways of being and knowing. These concepts were embedded in the expectations and execution of the students’ cross-cultural work.

Getting the Lay of the Land

Conveying traditional Hawaiian concepts to both non-native locals and students from the mainland US can pose a challenge. For example, in the Hawaiian worldview, land and nature are considered sacred, and there are profound connections between people and the land, sea, and sky. In contrast, Westerners tend to see land through the lens of ownership and use. Even concepts like community differ greatly; the Hawaiian concept of ohana (or family) contrasts with Western emphasis on individuality and autonomy. Time, too, is experienced differently in different cultural contexts. For Hawaiians, time is fluid and interconnected, whereas in the Western worldview time is linear.

But it is not only those challenges that prevent non-native students on the university’s campus from engaging with Hawaiian culture. In conducting their research, ID students found that many non-native students felt a lack of personal connection and have limited educational opportunities to understand Hawaiian culture. Cultural learning, too, is seen as secondary to their daily studies, and students who do not perceive themselves to be part of the campus community (for example, those who live off-campus) feel both physically and socially removed from the university.

Approach 1: WaiWai, A Walk in History

Changing student behaviors in hopes of changing their attitudes is likely a dead end. Better: change the way culture intersects with their daily lives.

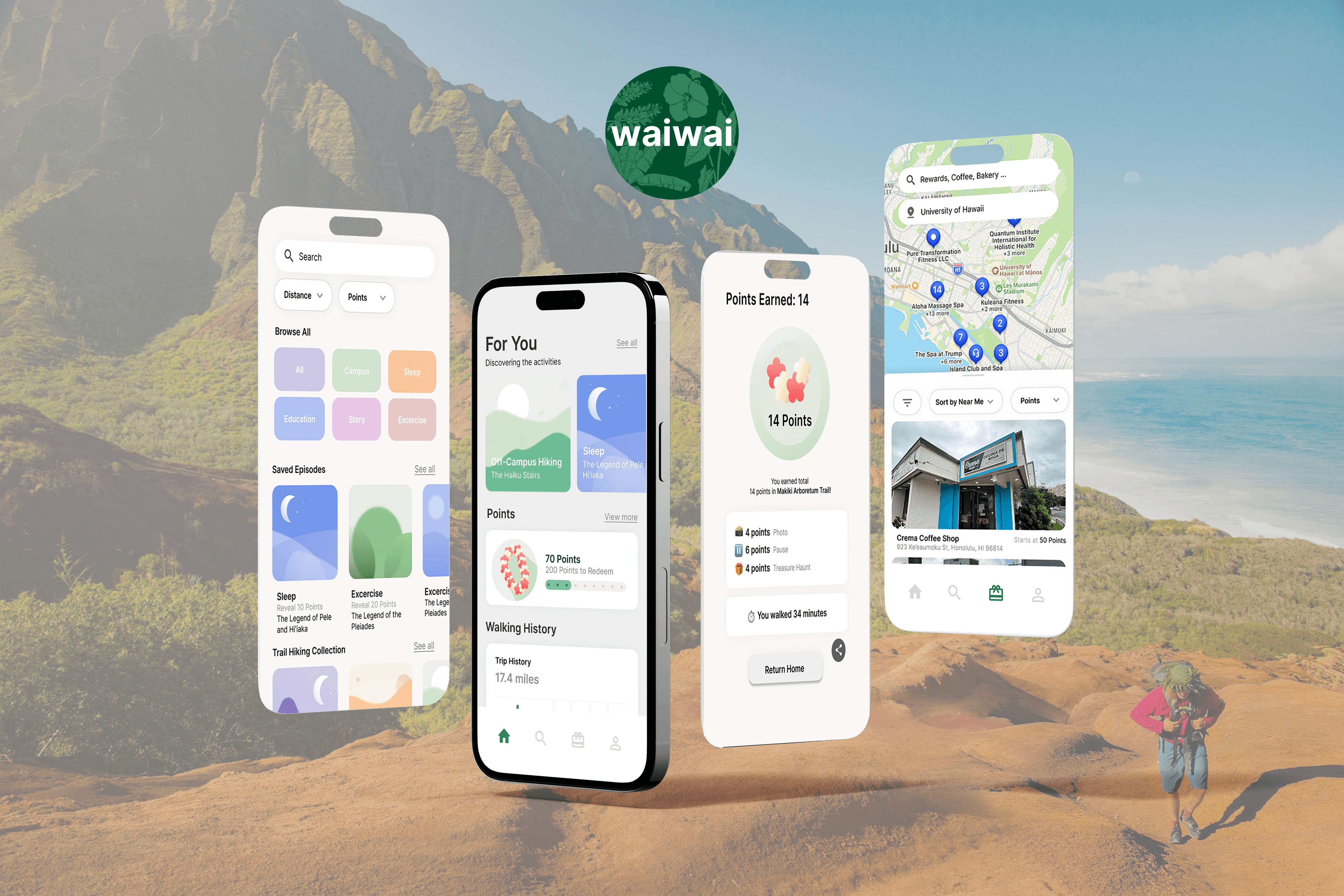

To do this, ID students imagine a unique, tech-driven, gamified interface for learning and engaging with Hawaiian culture and history that actively increases students’ connection to Hawaiʻi’s culture. Extended features and strategic partnerships would transform the experience into a gamified adventure that could support local businesses and foster a community-oriented ethos.

WaiWai is a tech-assisted guided walks program, and it offers University of Hawaiʻi students an enriching and immersive journey through Hawaiian culture, history, and the natural world. Through captivating audio storytelling activities—like capturing photographs, discovering meaningful objects, and pausing to be immersed in the sounds of nature—participants are encouraged to deeply connect with the essence of Hawaiian heritage.

Beyond the immediate impact on students, WaiWai is poised to forge new paths in educational technology. Its foundation in circular wealth principles distinguishes it from other platforms, bridging digital interactions with tangible community and environmental impacts. By merging technology with tradition, WaiWai also transforms the way students learn and live and empowers them to become custodians of their heritage and the natural world.

WaiWai App Demo

WaiWai, a guided walk program, offers University of Hawaiʻi students an enriching way to explore Hawaiian culture, history, and the natural world.

Approach 2: Building A Better Map

Western mapping also differs from a Kanaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiian) perspective, where there is a greater sense of fluidity and interrelation among places. Hawaiians’ sense of place is profoundly influenced by a network of interrelated and interdependent connections to the self, the environment, and the community.

This perspective is rooted in an intimate, reciprocal relationship with the land, which evolves through physical presence, land cultivation, and intergenerational learning. Hawaiian land division boundaries convey geographical features and different uses, but colonial boundaries often erase those relationships.

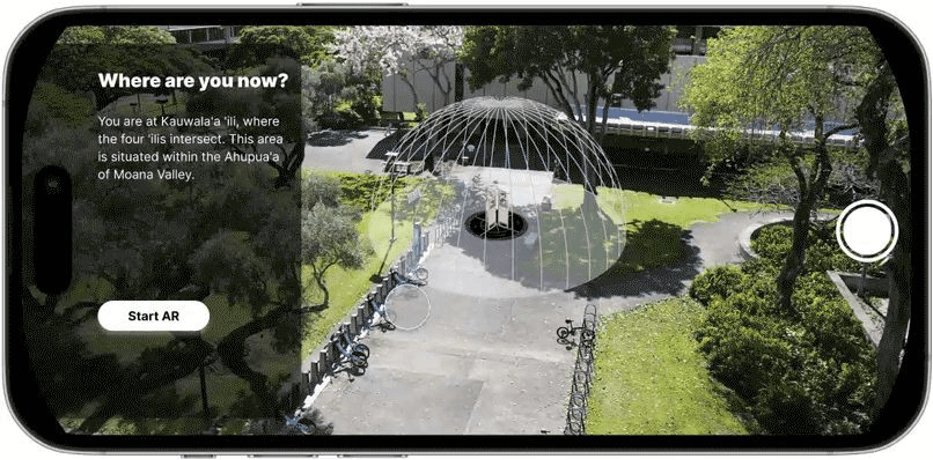

To help non-native University students gain a deeper understanding of these interconnected relationships, ID students sought to create a way to digitize the practice of “kilo,” or observation of the natural world. The goal is for students to witness how everything interacts and foster deeper connections to the concept of āina (land) and the Hawaiian worldview. From the Hawaiian perspective, the project explores how Native Hawaiians’ experiences of specific locations are shaped by various factors, including social, cultural, historical, and environmental influences.

Multidimensional Divides Demos: Understanding Place

The project features sequential learning that introduces students to increasingly immersive learning experiences to ease their entry into the educational process. It seamlessly extends from users’ digital devices. Adaptable video content can flexibly incorporate future concepts, accommodating shifting priorities or new directions that may emerge from user testing. And existing video can be expanded to broaden the scope and depth of the learning experience.

In practice, this content will be connected to existing campus wayfinding markers where video will be shown on a monitor, a placard, and via QR code.

This video demonstrates how the project communicates a Hawaiian sense of place, overlaying historical boundaries over current-day satellite imagery and 3D renderings of the island. The elevated and angled camera perspective also helps to orient the viewer as it enables a clear view of the southern shore, from the ocean to the mountain.

Multidimensional Divides Demos: Compass & Kilo

This video demonstrates how the project expresses the Hawaiian sense of kilo.

Multidimensional Divides Demos: Weather

This video demonstrates how the project conveys weather.

Multidimensional Divides App Demos: Direction

This video demonstrates how the project provides learners with a sense of direction connected to Hawaiian culture and heritage.

Multidimensional Divides App Demos: Observation

This video demonstrates how the project engages learners in observing their surroundings.

This solution offers captivating animations and immersive augmented reality (AR) experiences. The innovative visual format introduces Hawaiian concepts related to land division, space, and navigation through dynamic displays positioned near current wayfinding signs on campus called ‘ili markers, which ensures students’ learning is firmly rooted in their existing geographical knowledge.

Impact Beyond Campus

The opportunity to work with the Community Design Center at the University of Hawaiʻi allowed ID students to engage in a design challenge they would not encounter on campus. The class was able to experience firsthand intercultural engagement, and the resulting project uses design to contribute to greater equity and diversity.

Similarly, beyond the initial brief—which tasked ID students with visually communicating complex indigenous concepts, such as the land division system and non-instrumental navigation techniques—the project exposed students to alternative ways of presenting their ideas. Typically, ID students align abstract concepts with diagrammatic representations. Here, they were challenged to represent their recommendations in a way that is in better keeping with the indigenous, historical practice of experiential storytelling.

Both designs ultimately aim to educate but also preserve cultural elements at risk of being lost to modern perceptions of space and time. ID students’ approach can be replicated in myriad contexts and allows for the potential for a better cross-cultural and historical understanding of the land we inhabit, wherever we are in the world.

*The Institute of Design at Illinois Tech is located upon the territories of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, Myaamia, Kaskaskia, Bodwéwadmi (Potawatomi), Kiikaapoi (Kickapoo), and Peoria tribe ancestral lands, now called Chicago, Illinois.

Related

Tags:

Students

- Abigail Auwaerter

- Han Wen (Vanessa) Chang

- Isaac Jang

- Woo-Mi Jeong

- Eunji Kim

- Pitchaya Thaveesakvilai