If you’ve spent time in or driven through southeast Chicago or northwest Indiana, you’ve seen the miles of feathery reeds that grow along the highways and waterways of the South Shore corridor. While this common reed, or phragmites, appears picturesque and in sharp contrast to the area’s many heavy industrial sites, it’s actually the result of damage from these very sites. An invasive species, the phragmites chokes out native plants and destroys wetland habitats, reducing wild plant and animal populations.

Governmental and community groups have been fighting this plant for decades. But to an ID team led by ID associate professor Carlos Teixeira, this invader is an asset and an inspiration for the design of a new environmental monitoring device: the flag kit.

The flag kit translates environmental conditions into actionable data and is at the center of the Flag Calumet project. One of three partnered projects between ID and the Calumet Collaborative addressing brownfield redevelopment, Flag Calumet reimagines damaged habitats as sources of value.

The Calumet backdrop

Phragmites thrive in damaged ecosystems and take advantage of post-industrial areas like the Calumet region. Stretching from south Chicago and southwest Cook County to northwest Indiana, this region became a center for heavy industry—steel manufacturing, chemical processing, and oil refineries—in the 1880s. The area’s access to Lake Michigan ports and Chicago’s railroad hubs was attractive to industry and its nearly 400 wetlands were viewed as undesirable and unsuited for many other forms of development.

While manufacturers invested in the area through infrastructure and job creation for a growing middle class, their factories and refineries produced hazardous materials and runoff, damaging the wetlands, prairies, dunes, and other unique ecosystems.

As manufacturing declined in the 1970s and 80s, a long period of disinvestment began. Businesses and jobs disappeared, many residents abandoned the region, and a patchwork of post-industrial spaces was left behind. The most toxic of these are EPA superfund sites. Other post-industrial areas are classified as brownfields, defined by the EPA as areas where the redevelopment “may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant.” Brownfields present additional challenges to areas struggling with unemployment and extreme disinvestment.

Brownfields as value generators

In 2016, the Calumet Collaborative, a bi-state nonprofit, formed to address the complex network of social, economic, and ecological challenges facing the region. Two years later, the Calumet Collaborative began the Future of Brownfields project with ID, aimed at creating systemic approaches to transition the area to more sustainable development.

The project started in the Spring 2018 Sustainable Solutions Workshop, taught by Carlos and Andre Nogueira (PhD 2020), and facilitated by Weslynne Ashton, which explored the redevelopment of brownfields—specifically former landfills, vacant residential buildings, abandoned industrial sites, and contaminated natural areas—through new approaches that were deeply rooted in community involvement.

Often habitat remediation and sustainable development efforts ignore the socioeconomic and cultural aspects of an area, perpetuating extractive relationships with local communities and creating new social problems. Additionally, habitat restoration relies on specialized equipment and training, requiring outside expertise and shifting the center of knowledge about the land away from local communities.

To address this, the project team examined brownfields through multiple lenses—ecological, financial, physical, digital, political, cultural, networks, and individual—and asked how brownfields could empower residents, generate value, and connect residents to the natural environment.

As the class final report states:

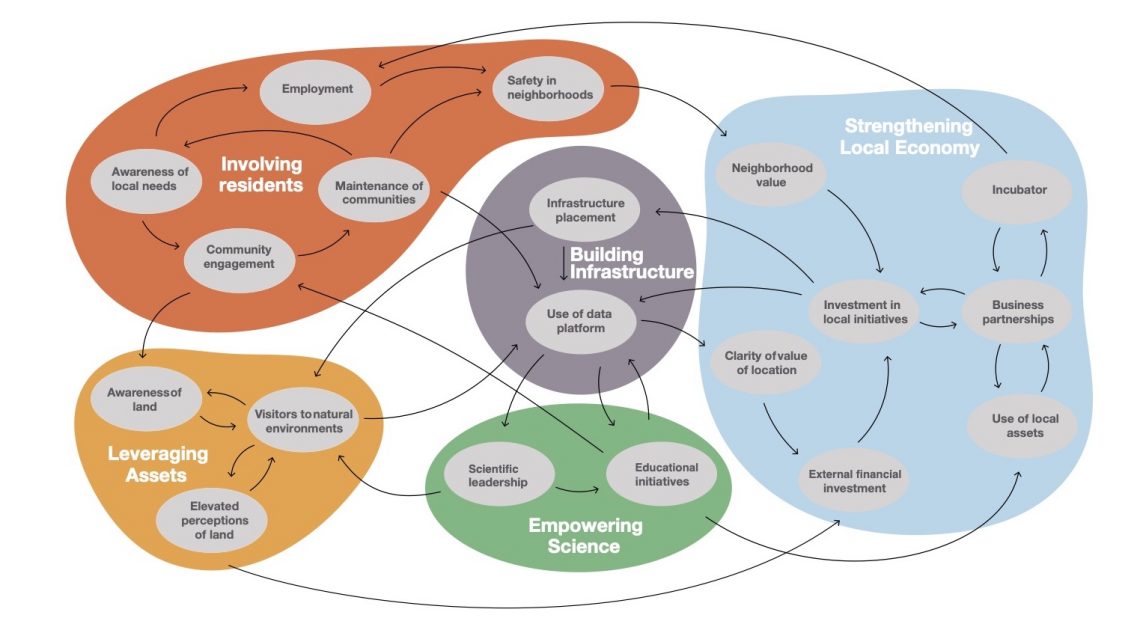

Ultimately, the class identified the following principles to guide the Flag Calumet project:

- Involve residents: incorporate local dynamics of daily lives into interventions, including making ethical choices for preventing displacement;

- Leverage assets: unlock the potential of existing initiatives in the region, as well as uncover underutilized resources that could be activated for regenerating the region;

- Empower science: increase local leadership capacity in applied scientific research so that new means for tracking and understanding interactions between socio-technical and socio-ecological systems can inform alternative evidence-based decision-making processes;

- Strengthen the local economy: recognize economic activities and ambitions of local residents so that they can directly benefit from and take ownership of new activities;

- Build integrated infrastructure: integrate the hard (tangible) and soft (intangible) dimensions of existing and new infrastructures to unlock current unsustainable practices.

Assembling the flag kit

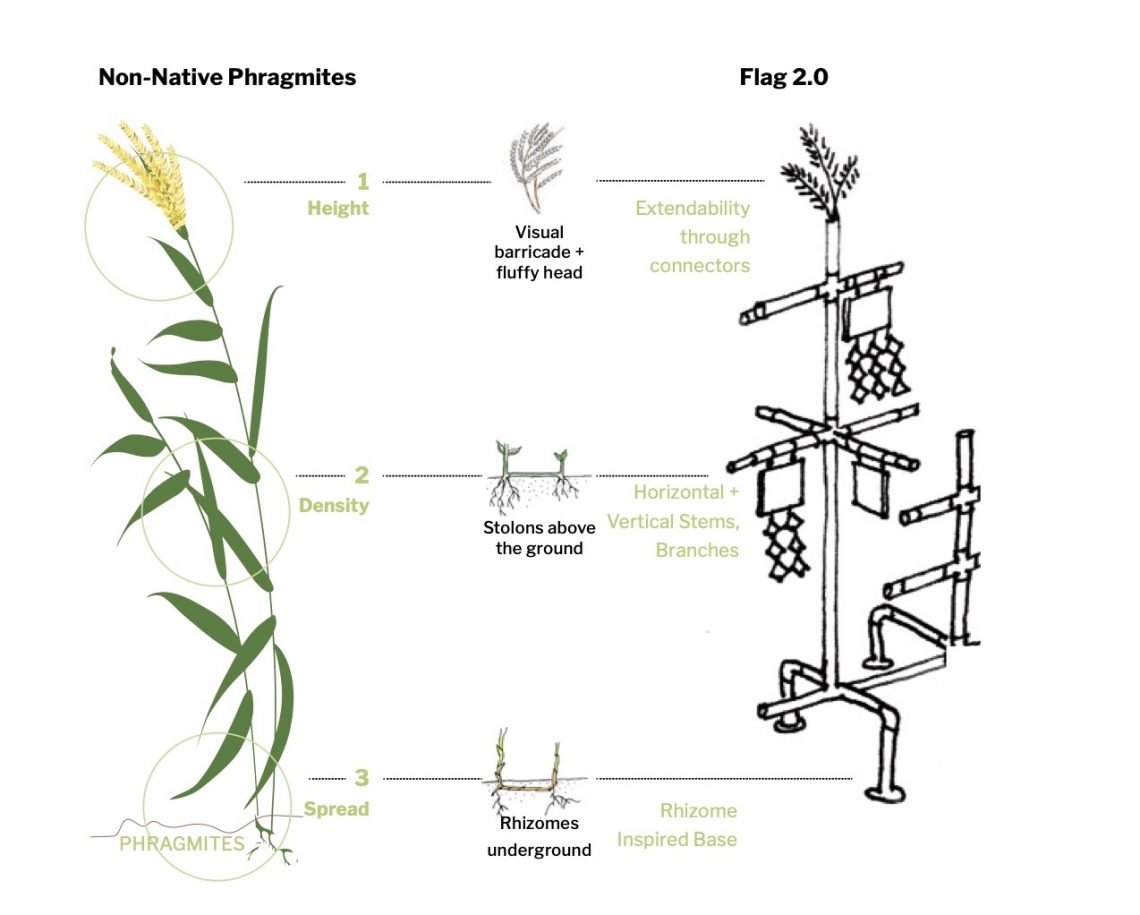

Using the phragmites as a model, the class conceptualized the flag kit as a modular device with a stem and branches, as well as a technical core to monitor the environment and collect data. Interaction with the physical device and its data invites residents to learn about the environment and participate in remediation efforts.

The kit offers residents a way to stake a flag, conveying a sense of ownership of and accountability to an area.

Prototyping the flag kit

With funding from the Chicago Community Trust, and in partnership with the Calumet Collaborative and the Field Museum, ID conducted prototyping engagements over summer 2018 with Field Museum Environmental Leadership interns at Big Marsh Park (near Lake Calumet in southeast Chicago). The flag infrastructure consisted of the hard dimension of the physical kit as well as the soft dimension of integrated curriculum for a flag kit assembly workshop.

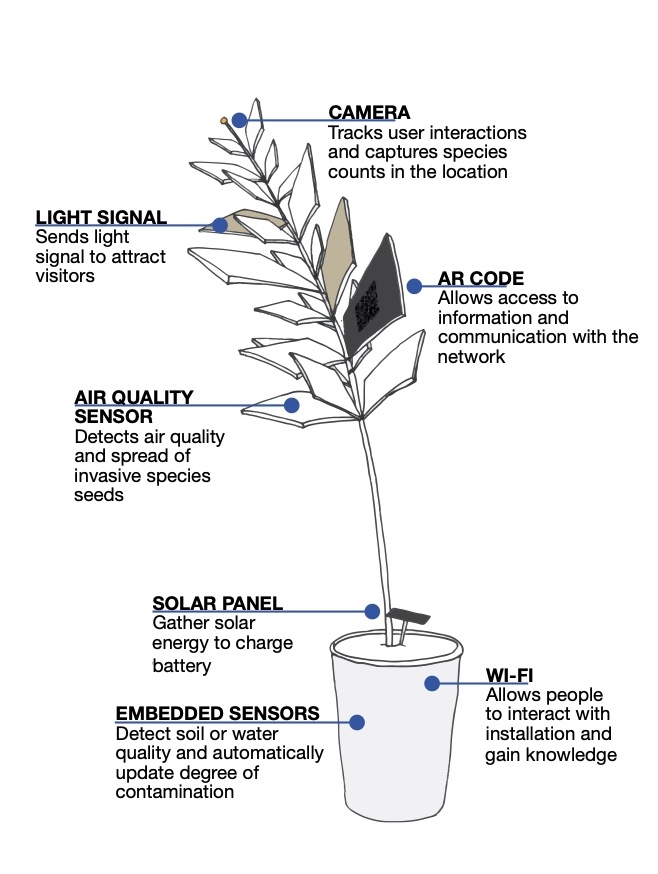

The kit was composed of a metal base and plumbing pipes for stems and branches. A technical core attached to the pipes and measured temperature, humidity, hazardous gases, and particulate matter, and also included a motion sensor and camera. Participants could take pictures and interact with the data through a touchscreen.

The physical kit provided a curricular focus for Field Museum intern workshops that incorporated natural science, computer science, and art. Building the stem and branches served as an entry point to natural sciences by exploring the structure of phragmites, their impact on ecosystems, and the industrial history of the area. Through assembling the technical components, instructors introduced computer science competencies, and once the kits were built, students used art supplies to customize and personalize their kits.

From here, the ID team recommended that the Flag Calumet project continue in the form of micro-pilots that would refine the design of the flag and address ways to make the data more accessible and useful.

Engaging communities in micro-pilots

In 2019, ID received a yearlong grant from the Kresge Foundation to advance the project with the Calumet Collaborative, the Field Museum, and the Wildlife Habitat Council.

The team expanded to involve a wide and diverse group of stakeholders, including:

- Community entities: Boxville Marketplace, Bowen High School, Claretian Associates housing

- Environmental organizations: Student Conservation Alliance, Indiana Dunes National Park Douglas Center for Environmental Education, Great Lakes Phragmites Collaborative, USGS Great Lakes Science Center, and the US Forestry Service

- Industries: Exxonmobil, Praxair, and ArcelorMittal

Through stakeholder engagements, the team mapped existing assets to understand the environmental services landscape and explored ways to involve residents with habitat restoration.

ID’s prototypes were iterated through a series of engagements—seven with the Field Museum, five with the Wildlife Habitat Council, two with Boxville Market, and two with the Student Conservation Association. These engagements demonstrated the limitations of the original kit, which was difficult to move to different sites due to the weight of plumbing pipes. Fiberboard was used for the final prototype, with the recommendation that it be replaced by recycled plastic from local producers in future iterations. In addition to providing a lightweight and versatile material, using recycled plastic would support local businesses.

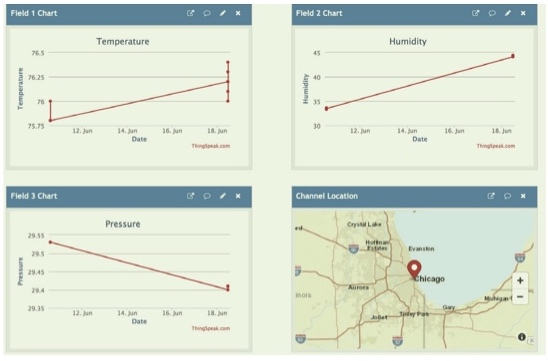

The initial flag kits accurately collected and stored sensor data, but that data was only available through the physical flag. In order to make the data remotely accessible, new prototypes replaced the firmware in the technical core, using open source NodeMCU, and added WiFi and a hotspot. The team created visual dashboards with ThingSpeak, an IoT platform. These changes make possible the eventual development of a digital platform to collect and aggregate data from multiple flags.

Through their micro-pilots, the ID team further defined the curriculum to be used with kit assembly workshops in industrial and community settings, classrooms, and youth programs. Like the Field Museum interns’ workshops, the curriculum provides instructors with topics and activities to develop participants’ competencies in natural science, computer science, and art as they assemble the Flag kit. Participants are encouraged to reflect on how these different disciplines can support socio-ecological systems as well as ways that they might contribute to habitat restoration.

Developing marketplace opportunities

Stakeholder engagements revealed ways that the project might expand beyond educational settings to provide an ecological services marketplace. In learning that local residents are rarely involved with habitat restoration, the team saw an opportunity to empower residents and provide jobs.

As Andre explains, “There is a high demand for habitat restoration and there is a high demand for jobs. Some [habitat restoration] jobs require high levels of expertise and specialized equipment—for example, if there is hazardous material in the habitat. Others don’t, like removing invasive species or applying healthy soil to an area without many nutrients.”

Through the data and dashboard visualizations provided by the flag, residents without specialized training could understand environmental factors and provide services. The flag would send alerts when action is needed to protect a habitat, like when phragmites are moving into an area.

“Phragmites is an indicator that you need to take action. With the solar panels, can we say that if the battery is not charging enough, there is a menace of phragmites. If you put the flag in a place with high humidity levels, then suddenly there is less water, it’s an indicator for potential phragmites,” Nathalie Cacheaux (MDes 2019) explains.

Residents could provide a service, removing the phragmites, protecting the local ecosystems, and thereby adding value to an area.

The flag marketplace would be enabled by a digital platform and could provide data to a wide range of stakeholders, including scientists and policymakers.

A model for future brownfield development

With the Kresge-funded project now complete, ID is exploring potential partners to adopt and continue the effort. Looking beyond Chicago and the Calumet region, the project provides a new, integrated model of social and environmental approaches to brownfield redevelopment.