51 Futures: A Community Project in Bronzeville

By Nuria Sheehan

April 2, 2020

When Crown Hall was erected in 1956 at the Illinois Institute of Technology, it was built on the remains of the Mecca Flats, a landmark apartment building and icon of Bronzeville’s era as the “Black Metropolis.” Constructed in 1892 for visitors to the World’s Columbian Exposition, the building sat on State Street’s racial dividing line. After the building owners ended a whites-only policy in 1911, the Mecca drew a mostly Black tenant base and became closely associated with the spirit and energy of Bronzeville, surrounded by the buzz of theaters and jazz clubs. It inspired Jimmy Blyth’s 1924 “Mecca Flat Blues,” Gwendolyn Brooks’s 1968 poem “In the Mecca,” and her poetry collection of the same name.

As Illinois Tech expanded in the 1930s and 1940s, the school purchased a number of area apartment buildings, including the Mecca, which were slated for demolition. Residents of the Mecca resisted. Tenants filed lawsuits against eviction and held out for fifteen years before the building was torn down in 1951.

As ID instructor Chris Rudd explains, “Placing Illinois Tech in Bronzeville displaced a lot of the cultural icons and spaces that were important to Bronzeville. That was a hard way to start a relationship. How do you start to repair that relationship? How do you start to give back to the community?”

The answer, as five ID students and faculty members found, isn’t through trying to fix or simply researching the community, but through community-led design. In community-led design, designers cooperatively share design tools with residents (or people who live in proximity to where interventions are being established) so that they themselves can lead the design process and create their own futures.

Building partnerships

When ID moved from downtown to Illinois Tech’s main Mies campus in Bronzeville in late 2018, ID studio professor Martin Thaler wanted his product design workshop to foster a reciprocal relationship between the ID and Bronzeville communities. In spring 2019, his class began a partnership with Urban Juncture, a community development organization dedicated to revitalizing Bronzeville. The project centered on Boxville, Urban Juncture’s marketplace where local entrepreneurs start new businesses by renting affordable shipping container spaces.

Marty’s class prototyped a set of modular wood boxes that Boxville could arrange as seats, tables, stages, or signposts to create welcoming spaces for visitors. In their final presentation, the class also recommended that the ID-Boxville partnership continue over the summer with a community design lab.

Chris Rudd

Beyond the lab

ID dean Denis Weil enlisted instructor Chris Rudd to head up the community design lab along with Master of Design students Matthew Impola, Justin Walker, and Yuqing Zhou. The ID designers rented a Boxville shipping container and created the 51 Futures design studio, named for Boxville’s 51st Street location.

The team quickly realized that a traditional design lab approach wouldn’t allow for the deep community engagement they were seeking.

With this shift, the ID team moved from a research to a service mindset, focusing on how to introduce design tools so that Boxville visitors and vendors could create their own futures.

“Design says let’s imagine what could be, it tries to open people’s minds to different ways [of thinking],” Chris explained in an interview with WVON.

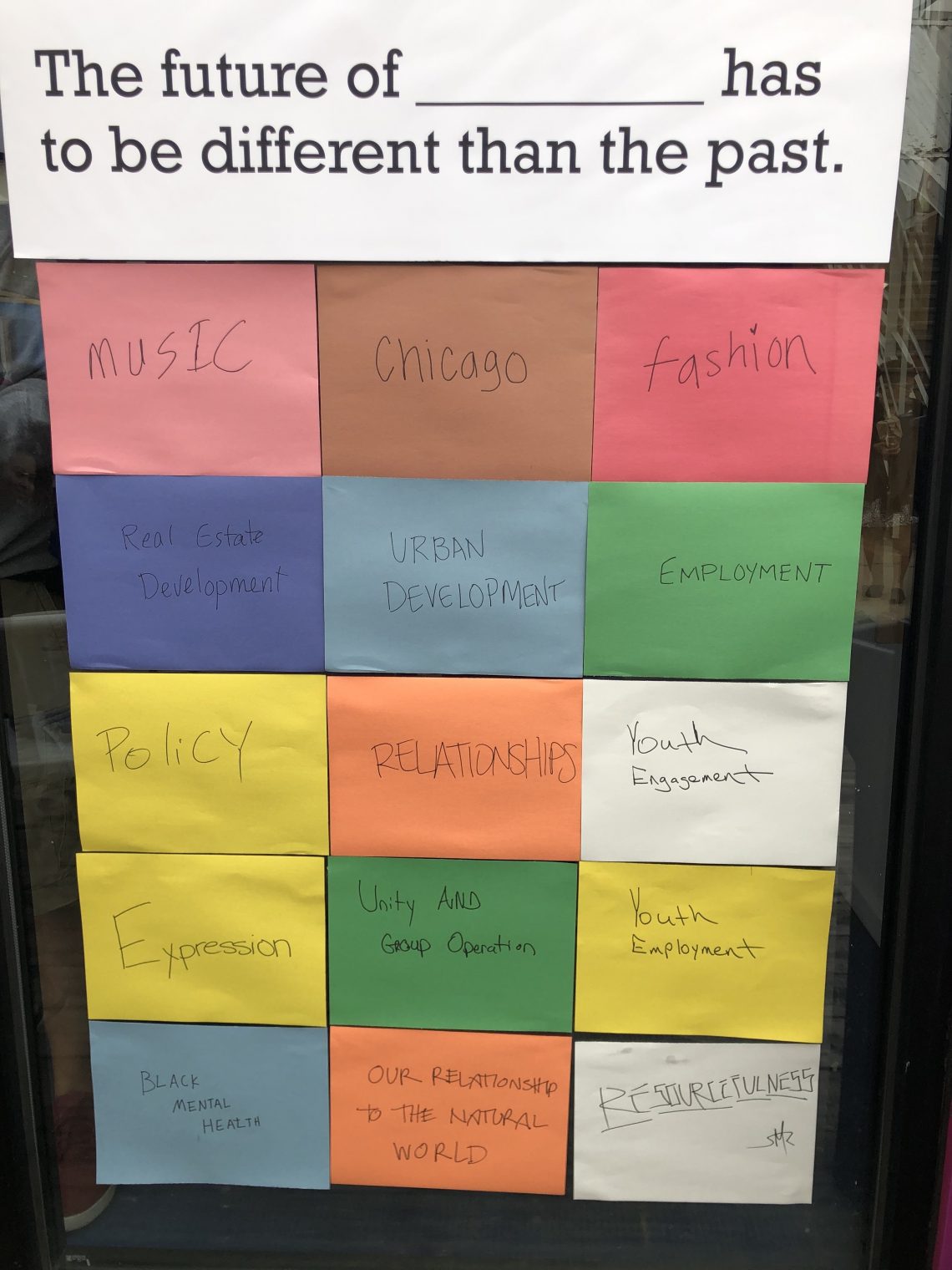

Community members leave responses to the future-framing statement.

Improving the perception of Black folks

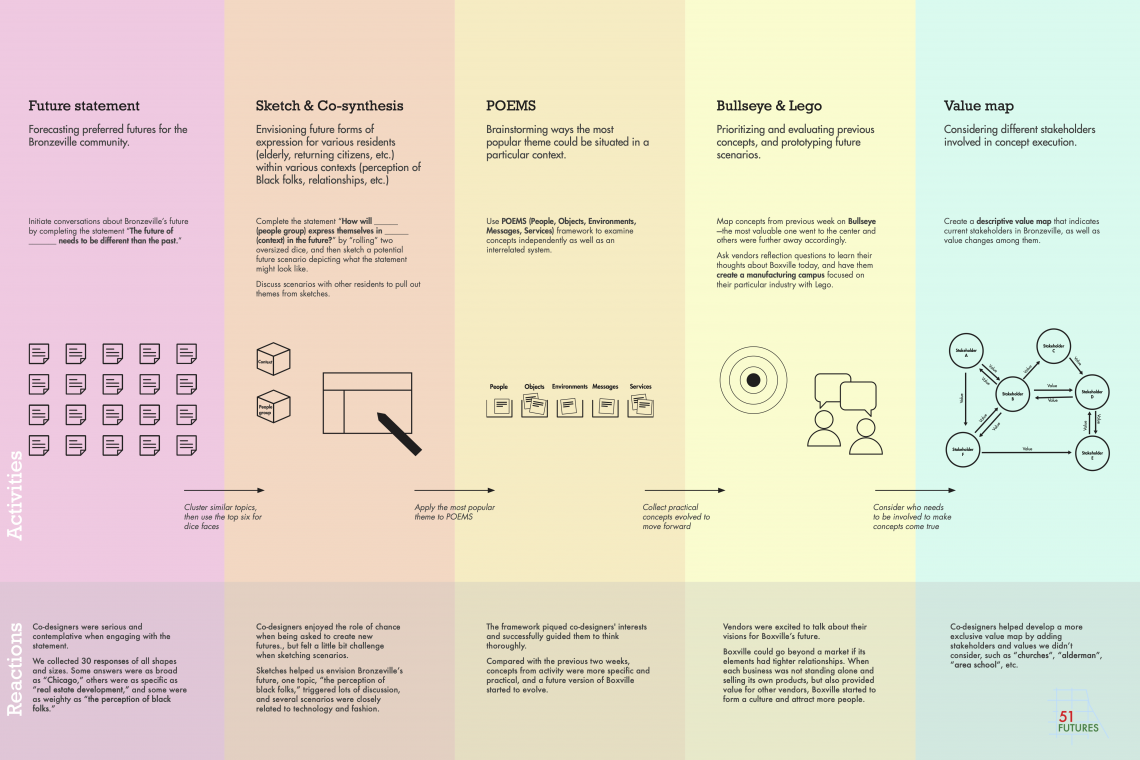

In order to facilitate the process of imagining what could be, the team began by asking Boxville visitors to complete this statement: “The future of _____ has to be different than the past.”

By focusing participants on what has to be different—rather than what should or could be different—the prompt encouraged participants to think beyond small-scale improvements to imagine a new future for their community. The prompt generated a wide range of responses, sparking further feedback and discussion.

One response stood out for the amount of questions and discussions it generated: “The future of the perception of Black folks has to be different than the past.” And so the question that drove all further activity for the design studio became:

“What would the future look like if the perception of Black folks changed?”

Confronting systemic racism

Flourishing as the “Black Metropolis” in the first decades of the twentieth century, Bronzeville attracted and maintained Black-owned businesses, a thriving middle class, and a vibrant arts community. The increasingly discriminatory policies in the 1930s, especially redlining—a practice the Federal Housing Administration began in 1934 that denied lending and insurance to prospective Black homeowners up until 1968—intentionally disinvested in the area, leading to segregation and economic inequality that continues to this day.

He says that designers must confront the racism embedded within institutions in order to address inequalities in a wide range of areas, including education, housing, and healthcare.

Chris describes these forms of systemic racism as a key component of governance in the United States, with implications for systems design.

Models for community-led and collective design

Community-led design offers methods to undo these legacies and repair previously extractive relationships. Rather than going into a community armed with ideas about what needs to be changed, community-led design supports residents in designing their own visions.

At 51 Futures, the approach went beyond community-led design, as visitors and participants changed from week to week at the Boxville studio. Chris refers to this process as collective design, with engagements built on the work of the previous group of community members, and other inputs, like the contributions of Boxville vendors, being incorporated. While this required the team to take time each week to explain their principles and their approach to design, it also gave the work credibility. Some were hesitant to participate with an outside institution until they learned that they would be contributing to the work of their neighbors.

For Chris, it was important to teach the students to be different kinds of designers than they had been in the past, to encourage them to learn from the community and build relationships through these principles of collective design:

Invite the community to be a constant part of the process. It was particularly important to maintain an inviting space in order to keep drawing in new co-designers.

Educate participants about the tools, processes, and how design works.

Support participants with visual clues, explanations, and encouragement.

Amplify the voices and thoughts of the community by showcasing their work in the studio.

Integrate the work by looking at it again the following week and explaining what had been established to new participants.

This form of collective design takes time and often does not fit into a typical design cycle.

“Teaching methods and frameworks takes a lot of time and effort,” Justin Walker (MDes 2020) said of the experience. “In certain times you’ll have to pivot; your co-designer will teach you something and will cause you to go back and figure things out again to move forward. There’s a lot of unknowns and you have to adapt, which can be uncomfortable.”

To foster trust, the team chose to be transparent, with all work done at Boxville. When the team worked in the box on non-market days, people could stop in and ask questions, or do any of the exercises.

“It did go a long way in terms of getting community members to trust us more. No matter how well intentioned you might be, when you go into a community that’s not your own, it’s difficult to be accepted and people might look at you skeptically. We were genuinely there to come and work with the community and not to provide solutions from the outside,” Matt Impola (MDes 2019) said.

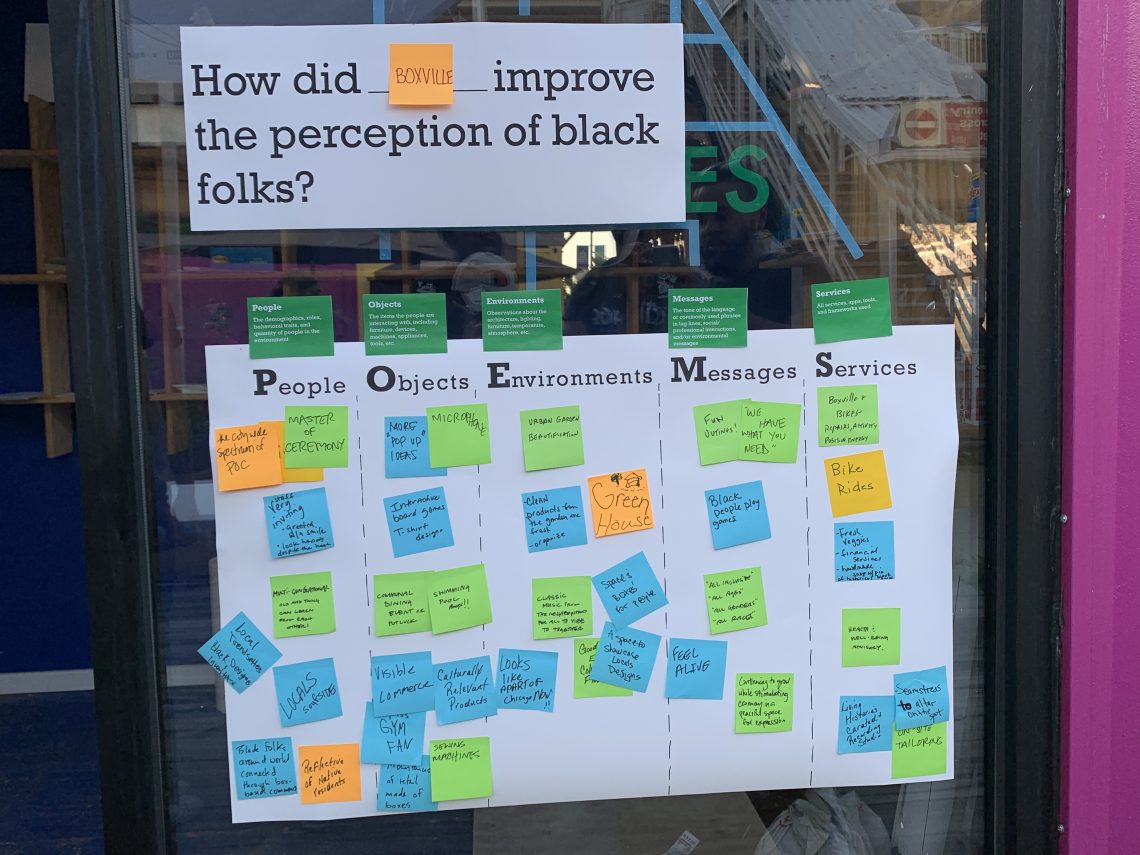

POEMS responses

Starting from the future

Starting with the question, “what would the future look like if the perception of Black folks changed?” the ID team told participants to go into the future, to imagine that they were in the year 2075 and the perception of Black folks was exactly what they want it to be. They were then asked: how did Boxville make that happen? Participants contributed their ideas using a POEMS framework, adding notes to each column to indicate which people, objects, experiences, messages, and services were required to make that future possible.

The responses centered around the ability to create a self-sustaining market, enabling the vendors to complete all of their business in the market. Fashion vendors, which are a major draw to Boxville, said they would want a tailor on site, a showroom. Out of these discussions, the concept of a marketplace focused on the fashion industry began to take shape. Bronzeville, once a music mecca, could become a mecca for Black fashion.

If such a goal could be achieved, all the vendors said, it would enable them to grow their businesses and hire people. While the team’s recommendations focused specifically on Boxville, the benefits of increased hiring in the area would affect a range of systems within the community, including housing, healthcare, and education.

At the project’s conclusion, the team delivered both the recommendations to develop Boxville as a market focused on a particular industry and advanced the original prototypes of the box structures. The updated boxes included a latch system so they could be built into usable stages and signal towers for advertising.

The next chapter

Chris envisions future uses for these structures across the city.

“If those kits were dropped in Black neighborhoods, would residents use them to advertise an event or a rally? That would be the next iteration to figure out. How could the kit advance civic engagement for communities? How could our infrastructures support this?”

Beyond the structures themselves, Chris continues to shape the emerging field of collective design by training new designers and developing relationships between institutions and communities. He hopes to expand collective design , adapting the 51 Futures journey map so that other areas of Chicago can develop their own future statements, envision paths to those futures, and develop new knowledge and awareness from within.

Journey Map

At Boxville, the ID-Bronzeville relationship had shifted by the conclusion of the eight-week project.

“When we first started, it was this new thing, we were just these folks from IIT,” Justin explained, “But by the end we had become part of Boxville. That transformation came from us trying to be as open and transparent as we could. And from trying to give as much as we could anytime that we were there.”