Transforming Chicago’s Food Ecosystem for Everyone’s Benefit

By Stephanie Hlywak

March 31, 2021

Few essential systems are as invisible to consumers as the food production and distribution infrastructure in the US. Shoppers take for granted that produce, meats, and packaged foods will be waiting for them at the grocery store, and diners are largely unaware of the journey their restaurant meal took to get to their plates.

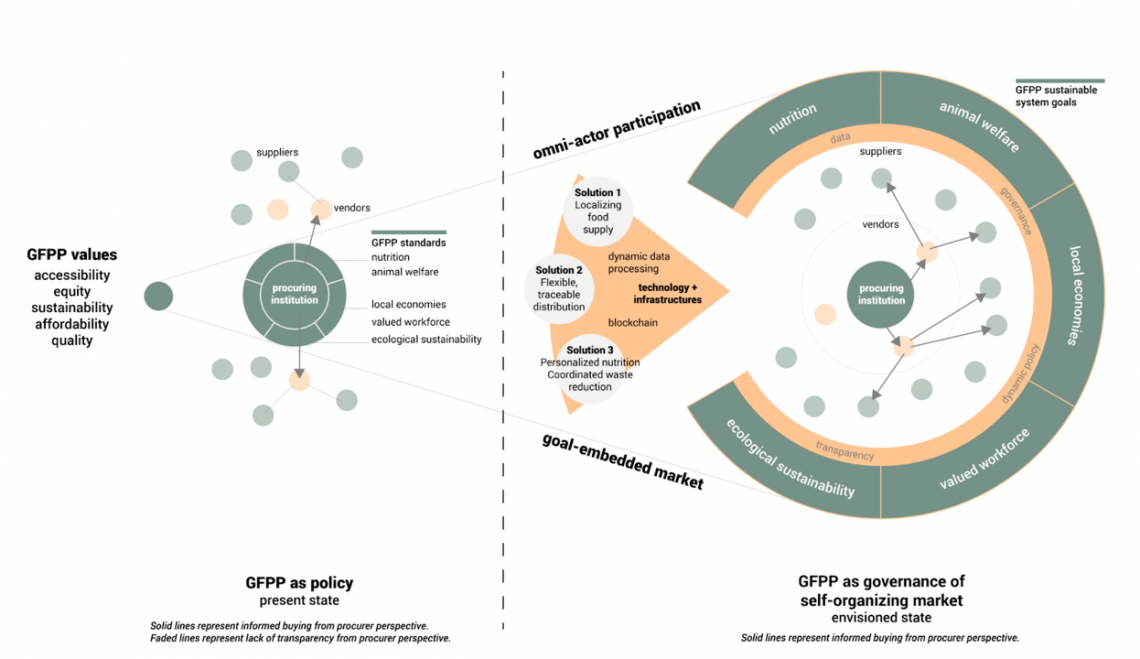

But to designers, these complex systems are ripe for study—and improvement. After all, the modern food ecosystem relies on outdated industrial agriculture practices and prioritizes low prices and mass quantities over collaboration and justice—to say nothing of issues of equity, accessibility, quality, nutrition, animal welfare, and fair labor. Frameworks like the Good Food Purchasing Program (GFPP) allow public institutions to leverage their buying power to drive systemic change. But policy isn’t practice.

GFPP present to future state

How then to bridge the distance between intention and implementation?

That was the question graduate students and faculty recently confronted as part of the Sustainable Solutions Workshop at IIT Institute of Design (ID). Over the course of a 14-week collaboration between a variety of community partners involved in the Chicago food ecosystem, students were challenged to develop infrastructures to support the goals of the GFPP, which was adopted by the City of Chicago in October 2017. But they soon realized to succeed they would need to define an equitable and sustainable system for the movement of nutrients throughout Chicago.

Exploring, experimenting, and envisioning

To tackle the project, designers began by understanding the complex challenges and assumptions that underlie the current food system in the United States. In the process, they identified five areas in the current system where intervention is likely to have a high impact: production, distribution, procurement, consumption, and disposal.

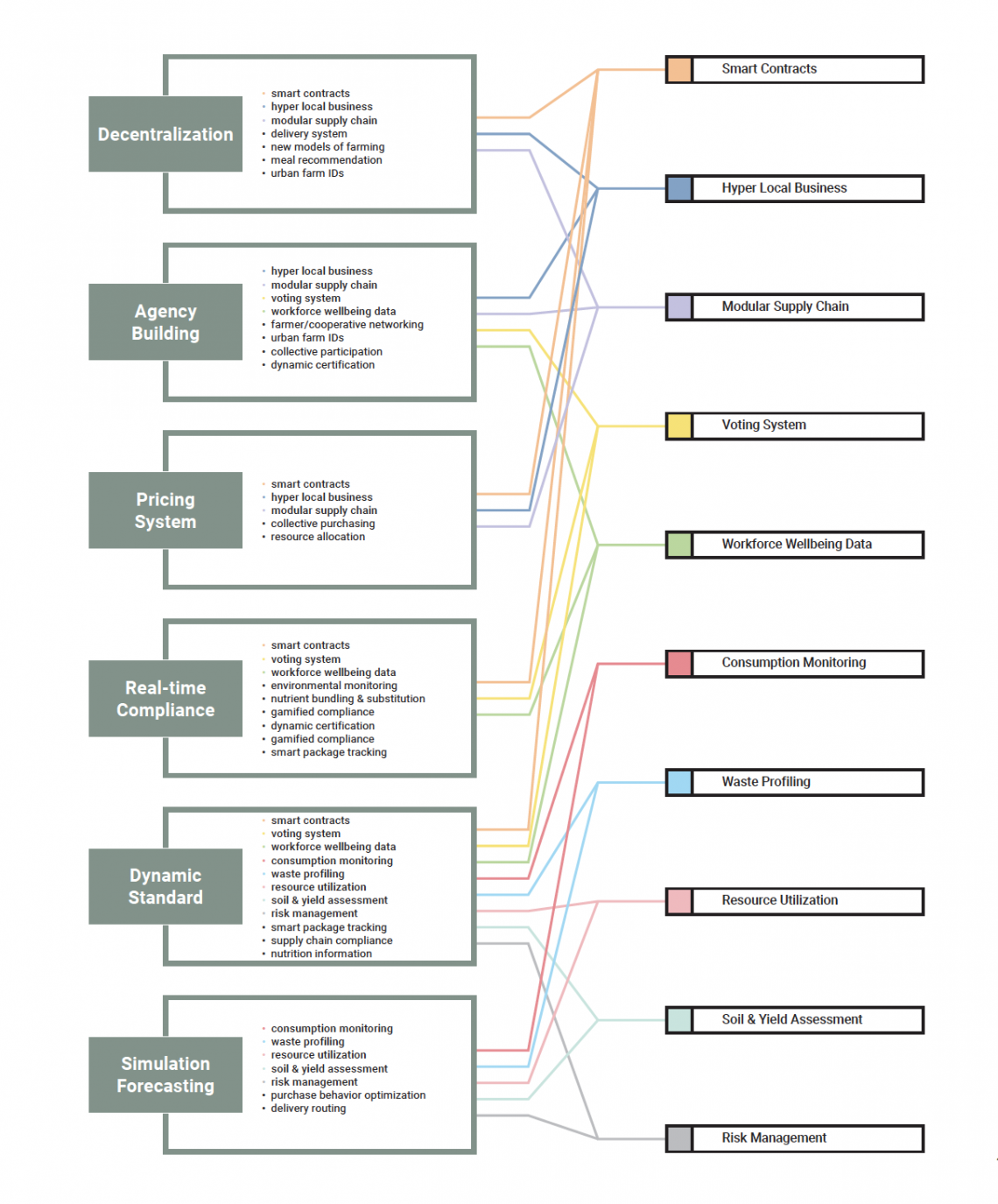

ID students took a non-linear, prototype-led approach to examine and respond to the social, cultural, natural, political, manufactured, financial, digital, and human implications of their proposals. After 12 weeks of prototyping and evaluating, students categorized their insights into six abstract concepts—decentralization, agency building, pricing systems, real-time compliance, dynamic standards, and simulation forecasting. They cross-referenced these concepts against GFPP goals before proposing solutions.

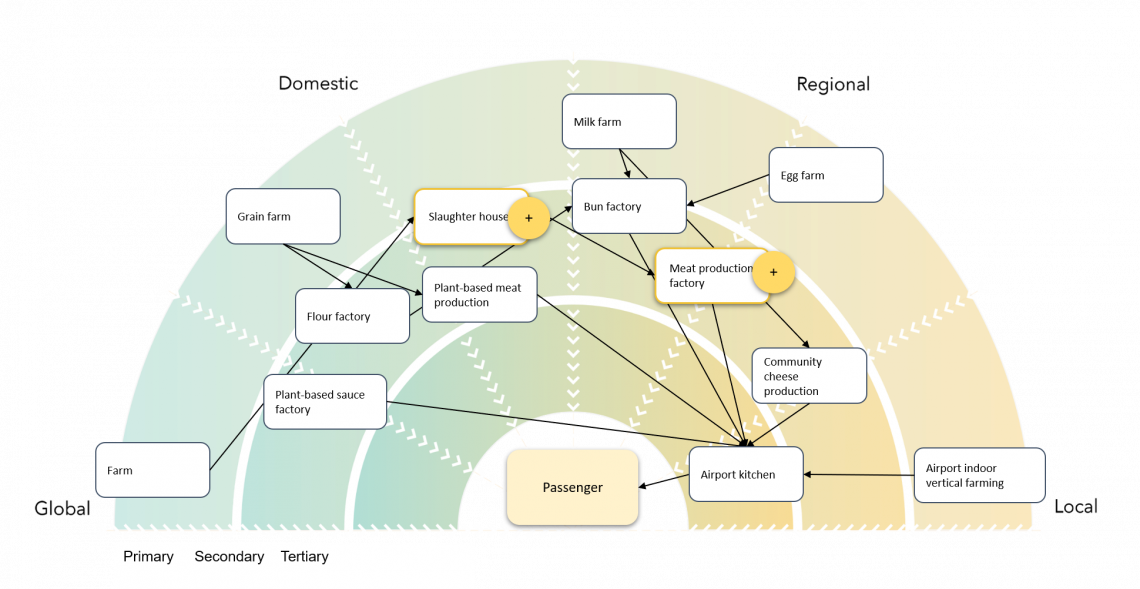

The solutions that the students suggested necessitated four macro-level paradigm shifts: away from standardization and mass production toward made-to-order, small-scale, batch-based offerings; away from a rigidly designed supply change toward transparent, agile forms of distributed production; away from subsidized single-source calorie-rich foods (e.g., dairy, refined grain, meat) toward crop diversity among nutrient-rich foods (e.g., vegetables, fruits, fish, and whole grains); and reframing the choice of healthy, nutritious food as a central to ethical and culturally enriching eating practices.

A system of solutions

So, what does this look like in practice? How can design help transform deeply embedded processes and relationships?

To set the stage, the students envisioned a future in which the goals of GFPP are embedded into a structured marketplace (i.e., a platform or set of platforms) in which not only buyers but suppliers are encouraged to engage in transactions of mutual self-benefit. To achieve that, they identified the need for new markets, behavioral incentives, modes of production, governance models, distribution systems, and infrastructures.

All of that requires rethinking how we track, score, and monitor food production, consumption, and waste. To facilitate the transfer of relevant economic, environmental, and consumer data, students proposed blockchain, a technology that creates a distributed ledger of records open to all members of the system. This approach lowers barriers of entry to local entrepreneurs and cooperatives, while the application of real-time scoring systems around GFPP compliance enables the marketplace to drive towards socially just practices that facilitate the distribution of nutrients to undernourished areas.

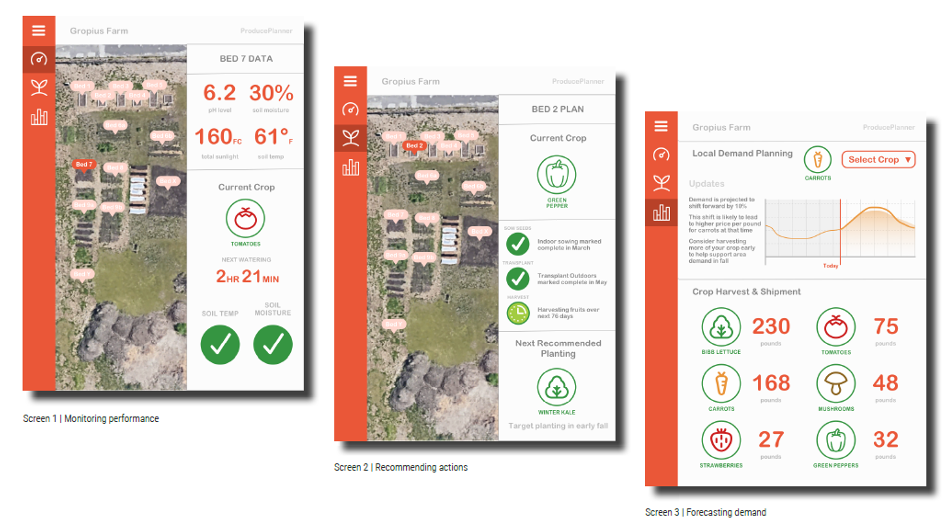

In practice, this means that a stagnant city brownfield could be transformed into an urban farm that provides meaningful, equitable work for historically disinvested communities. Imagine a lot dotted with sensors that supply real-time data on light quality, soil moisture, PH, and temperature; farmers outfitted with demand projections; and food products containing unique identifiers to track their movements through the system.

Monitoring performance, Recommending actions, Forecasting demand

From there, vendors track their inventory alongside real-time GFPP scores through a smart contract platform, and QR code labels enable food consumers to access the farm-to-table journey of each ingredient and see a meal’s nutrient profile. Consumers could personalize their meals to suit their cultural-, lifestyle-, and taste-based preferences. This focus on choice over availability or scalability opens the door for more locally prepared and balanced meals—all made from ingredients that began on that former brownfield.

The work of students in the Sustainable Solutions Workshop exemplifies the ID approach to humanist and future-oriented graduate education that emphasizes advocacy and leverages emerging technologies to deliver a more just, sensible, and equitable reality. In outlining sustainable solutions designers believe could create systemic change, they’ve proposed transforming the food ecosystem of Chicago from one in which low prices and mass quantities prevail to one focused on collaboration and justice—and one that benefits all participants, from the producer to the partaker.

Tags:

Students

- Harini Balasubramanian

- Justin Bartkus

- Justin Walker

- Todd Cooke

- Jessica DeMeester

- Audrey Gordon

- Grace Hanford

- Alvin Jin

- Zhongyang Li

- Shuyi Liu

- Jason Romano

- McKinley Sherrod

- Brian Siegfried

- J Smyk

- Yutian Sun

- Xiaoqiao Tang

- Shiya Xiao

- Wanshan Wu

- Yueyue Yang

- Andreya Veintimilla

Faculty

Technology & Data Consultant

Teaching Assistant

Partners & Collaborators

Center for Good Food Purchasing

Chicago Department of Public Health | Jennifer Herd

Chicago Food Policy Action Council | Rodger Cooley, Marlie Wilson, & Aasia Castañeda

Chicago Park District | Rebecca Tsolakides

Chicago Public School | Harold Chapman

IIT Stuart School of Business | Weslynne Ashton

YMCA of Metropolitan Chicago | Marjorie Kersten & Meg Helder

New Futures Lab (Fabri-Kal) | Bill Robinson & Kate Robinson