How Does Someone Become a Designer?

By Jarrett Fuller

February 15, 2023

Foundation courses in art and design schools are perhaps one of the most enduring legacies of the Bauhaus. When László Moholy-Nagy started The New Bauhaus in Chicago, he reinstated these courses as core for all students. I took foundation courses when I studied graphic design 15 years ago and many design students today — across countless design fields — still enroll in these classes. But what is the purpose of foundation? Why has this model endured? How should foundation classes today train future designers?

In this conversation, I speak with ID faculty members Tomoko Ichikawa and Martin Thaler. Martin and Tomoko teach the Foundation sequence at ID, bringing distinct backgrounds to the program. Martin has taught product design and environmental design full-time at ID since 2008 after a career in industry working with clients including Motorola, Gateway, and McDonald’s.

Tomoko has taught at ID since 1993, becoming a clinical professor in 2017. Her classes focus on communication design and visualization. She was previously an information designer at Siegel and Gale in New York, and Doblin Inc. in Chicago.

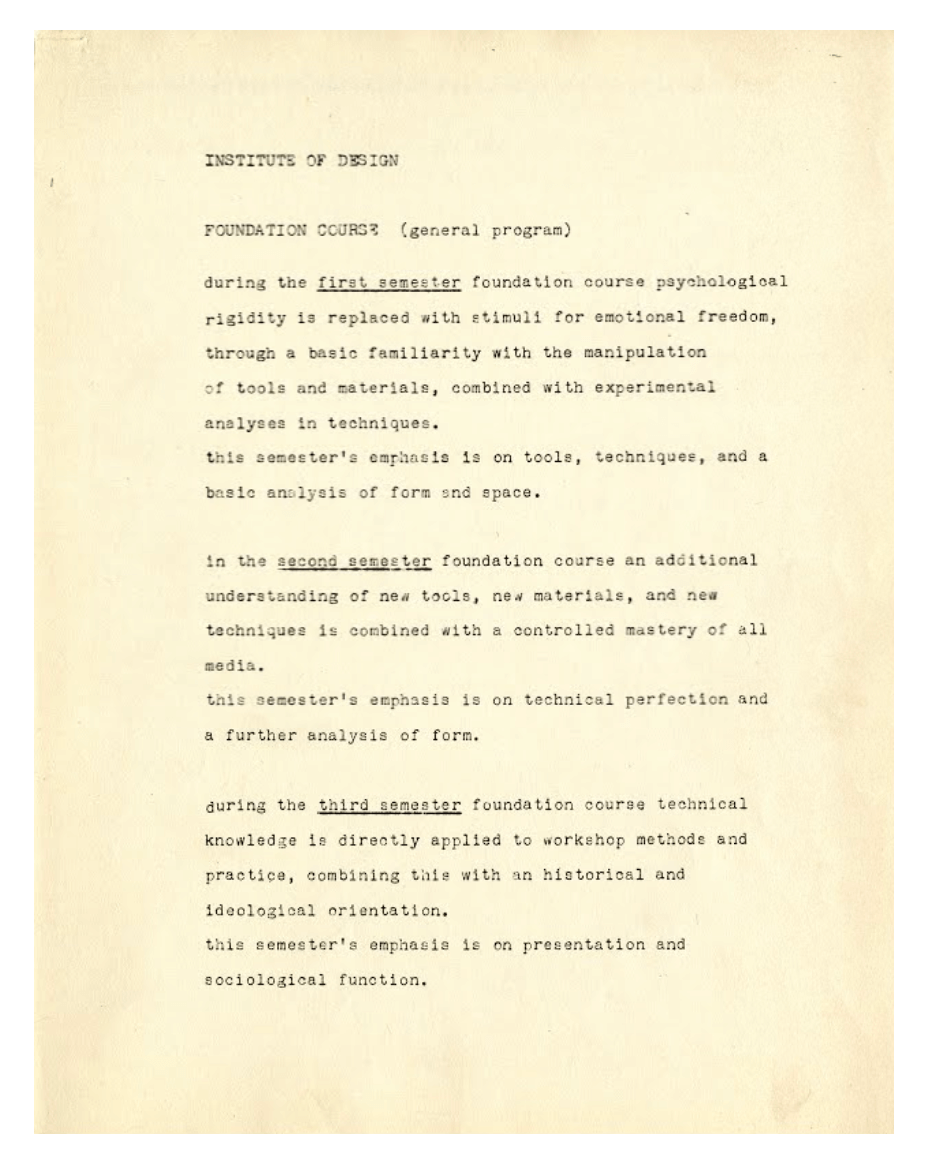

Moholy-Nagy memo on Foundation courses. University Archives and Special Collections, Paul V. Galvin Library, Illinois Institute of Technology.

JF— One of the legacies of the Bauhaus was this idea of the Foundation courses, this set of courses that every student would take to level set and give everyone a sense of both the tools and ideologies, as well as ways of thinking to be a designer. This is something that Moholy-Nagy brought over when he started what is now the Institute of Design.

I found a memo of what would be taken in the Foundations courses when the school started. In the first semester, he writes that the emphasis is on tools, technique, and analysis of form and space. The second semester is on technical perfection and further analysis of form. And then the third semester is on presentation and sociological functions. Hearing that, how does that resonate with how you think about Foundation courses today at ID?

TI— I use a framework at the beginning of my first week to situate the students in terms of what they’re learning over 14 weeks.

The first five weeks are all about elements and concepts. What are the elements of two-dimensional design? Typography, graphic elements, imagery, etc. What are the techniques and concepts? How do you know when you have contrast? What do you do to attain visual hierarchy?

Then the second five weeks of the class are about applying actual information content matter. It is about analyzing the information and figuring out how you use those elements that we just taught you in the first third of the class.

The last capstone project is about understanding the social context. We do a live project using a real scenario with a piece of equipment that is lacking in terms of good visual design and we try to get the students to work on that.

And when I saw this document, which I didn’t know about, I thought “Wow, it’s kind of alarming that I’m still using that basic framework!” I don’t know if that’s good or bad. We have some evolution, yet there are some things that are perennial. I think the Foundation program is a bridge from the non-design world into a design world so that students can be proficient enough to go into the main MDes program.

JF— I think that the perennial nature of these ideas is the key here. You mentioned that your class is focused on communication design or graphic design: typography, contrast, layout, etc. Marty, you come from an industrial design background. What’s happening in your Foundation class?

Marty Thaler and students in a workshop.

MT— My class is also very Foundational and I also see it as a bridge. What’s wonderful about it is we get people from all areas. It’s one of the few programs at the graduate level that welcomes students from every background. They can enter the school without a design background which makes for very interesting work. Many people come to the school and have never built anything, made things, or have the know-how needed to actually build prototypes and physical objects. The philosophy of the school is that people need that knowledge because it’s a way of thinking as a designer, whether you end up designing objects or communications or strategies or service design. And I’ve always thought that all those principles are interconnected. There is some underlying structure there.

We start with very basic modeling techniques with chipboard. It used to be foam core but I’m a little concerned about the environmental impact of foam core so I just said no more foam core. We follow a similar process to Tomoko’s class: We try to progress slowly from the early stages of making simple objects to a more complete, complex problem that we solve towards the end of the semester. It does take time. It’s a field that needs iteration. You can’t jump to something very difficult, you have to start with the simple things and then progress. That’s a struggle.

TI— Foundation is five different classes. Marty teaches Objects and Artifacts and I teach Visual Communication. But there’s also Photography and Interaction Design. All the Foundation students need to take all four classes. The idea is that we’re trying to make them more well-rounded design students so that they can enter the MDes program. The students that we get coming straight into the MDes program who have a background in design are often highly specialized — they’re either web designers or graphic designers — and they lack that well-roundedness, which we think is required. Our Foundation students bring in a lot that is not of design too, and that’s extremely valuable.

JF— Could speak a little bit to this interdisciplinarity of design? Your students are coming in with either a highly specialized form of design or no design background at all and they’re all going to be mixed together and they’re all going to do different things. How do you think about what students should know as they go through their time at ID?

TI— I think that what we’re asking our students to do is not the end product. Because we are a graduate-level school, the things that they think about are much more complex, things that have to do with sustainability or healthcare, and civic design. The idea is that we are training our students with these Foundational skills so that they can then participate in that larger thinking and communicate broad ideas, either through diagramming or good communication design skills, or good prototyping skills. So it’s not about perfecting the product design skills and it’s not about perfecting the two-dimensional design skills. It’s so that they can then apply them to much bigger things.

MT— What I emphasize in my Object and Artifacts class is understanding the design process itself. It’s about an approach, a way to communicate your ideas, creating a way to think about them and present them so that people can work together. So the other thing they get out of Foundations is that there’s a real strong sense of community that’s built. Foundation students have played a strong role in the culture of the Institute of Design.

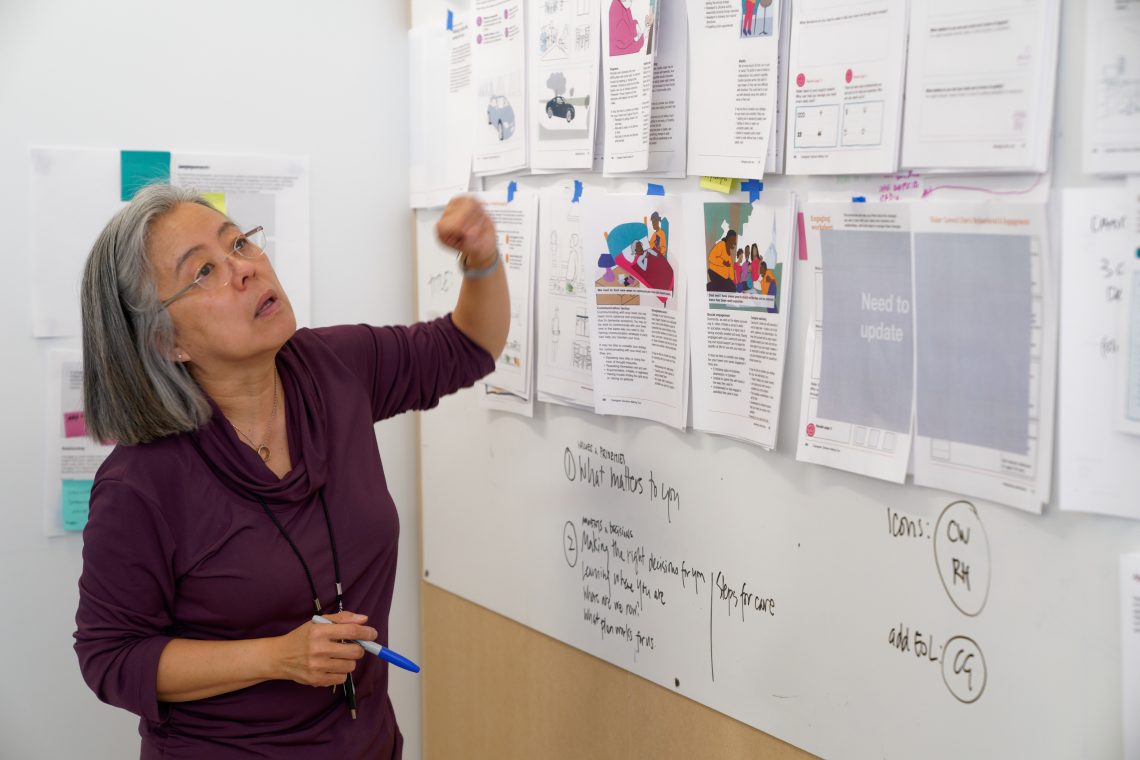

Tomoko Ichikawa workshop

JF— This makes me think about how so much of design is increasingly intangible — it’s about creating services or systems. It’s hard to actually look at the thing that has been designed. How do you think about that in the Foundation classes? For example, when you’re doing modeling, and thinking that a lot of these students might end up designing things that don’t actually have a physical form?

MT— When you deal with the tangible thing, it’s easier to explain the values of this detail or the way that it fits into a system. Our last project, for example, is about the future of work. It started years ago, more as “Let’s do the next generation of an in-office product that holds your papers under your desk like in the old days.” Then, of course, it’s become very topical and much more interesting. Now the students get to learn to think about how their object can help people, whether it’s going to help them do their work in a hybrid work environment or a range of other contexts.

TI— The idea is that we have to communicate these ideas really well so that people can envision what it’s going to be like. That’s where the communication design comes into play. It’s not graphic design, it’s communication design. It’s very purposeful and intent-driven. Iterative prototyping is alive and well! How do we get people to iterate where every iteration gets better and better and moves the idea forward? The ability to communicate your ideas to whomever you are with, even if it’s to your own teammates so that you can get alignment around them, that comes from understanding what you are trying to communicate. It’s intent-driven communication rather than form-driven communication.

This speaks to critique too. Students are very fearful at first because they often don’t come from a critique culture. So even teaching them the right kind of language, that it’s not personal, that we don’t use “I like” or “I don’t like”. The bigger goal, then, becomes elevating the work of a team. Big design projects are not possible for one person to solve alone and there are always going to be other people that they’re going to be working with.

So it’s not just craft but also about their thinking and approach. Then, maybe, even their own identity changes somewhere during the semester where they can say “I am a designer now” as opposed to “I am an electrical engineer.” We try to foster those moments where they can recognize that transformation within themselves.

JF— Where, if at all, does software and technology fit in here?

TI— Tools are tools and the idea is that we use tools as a means to accomplish things. Understanding the basic principles of design such as contrast or visual hierarchy, composition, and layout, it doesn’t matter if you do that in PageMaker or Quark or InDesign, or even do it by hand if you want to. It’s about being able to understand what it is that they are trying to accomplish, what kind of principles they want to apply, what kind of approaches, and then the tool just becomes a way to serve that aspiration.

MT— One thing that we introduced a long time ago was having a sketchbook, which was just fantastic. We encourage students to use their notebooks to keep track of their ideas or develop ideas and use paper. I think because of the digital nature of what they’re doing, it’s harder to get them to draw.

TI— Is it harder because they want to sit in front of the computer first? But if you get them to understand the process, I think they understand that you should actually work out a sketch first. I always tell them that the computer programs actually are prematurely asking them to make decisions about things before they even know. I require my students, along with their finished digital assignments to provide sketches of their idea development. My co-instructor, Jody Campbell, who I teach the class with, and I are firm believers that this is an important step for them to do first. There have been studies done where the hand, eye, and brain coordination is actually very powerful and it helps you to think about things that you may not when you’re sitting in front of a computer. Physicality is absolutely critical and I think it’s because it’s on all the time. It’s there in front of you all the time. Whereas if you’re working on your computer, you turn it off and you close your laptop and it’s gone.

JF— I watched a beautiful commencement speech from one of your former students, Justin Bartkus, and he had a line in there where he says, “ID doesn’t erase our unique set of skills, experiences, and quirks, rather it embraces them, equips them, and amplifies them. We come as engineers, architects, business folks, theologians, and we leave as engineer-designers, architect-designers, business-designers, theologian-designers.” He calls this “the dash-designer”. Could you talk about how you think about teaching these sets of skills, teaching these ways of working, teaching these processes, while also embracing and encouraging and incorporating this range of experiences that every student is bringing in?

TI— I think they’re coming to the Institute of Design to become something bigger and they’re coming to the Institute of Design like Marty said, not to become product designers or graphic designers. So they’re bringing their collective background and during the time of Foundation, it’s like we’re asking them to squeeze into and hyperfocus but once they get into the main program, they expand back out again so that they could work in this much larger context of the world. I love Justin’s articulation of that, the dash-designer or the design+. It goes back to the idea that design isn’t really for design. Design is for the world. Design always works with other disciplines.

Foundation students come and see the other design students doing incredible work and they often feel bad about that. They think they come from a point of deficiency: “I am not a designer, I don’t have the design skills.” We try to encourage them to say, “Well, you have all these other skills. It’s not a deficiency. It’s layers where you are taking what you bring and then layering design on top.

MT— I try to emphasize to them, even if they didn’t go to a traditional design program, that they do have a beginner’s mind. That can be a real advantage if you use it properly. We’ve seen it over and over again.